A Textual Variant in Psalms 38:12c (LXX) Traced from the Earliest Greek Manuscripts to the Modern Liturgical Psalter

Filipp Porubaev

September 14, 2024

In May and June 2024, I had the valuable opportunity working on my dissertation as a guest of the “Editio critica maior des griechischen Psalters” project (the Project), which has been under way in Göttingen since 2020. The aim of the Project is to publish a new critical edition of the Greek Psalter, a more complete one than the Psalmi cum Odis of Alfred Rahlfs (Göttingen, 1931).1 This challenging task is becoming feasible thanks to a unique catalogue prepared by the Project team, which offers descriptions of about sixteen hundred Greek Bible manuscripts, most of which contain the Psalter.

Whereas the Project reconstructs the original text of the Greek Psalter (Old Greek), my research focuses on the most recent stage of its textual tradition, namely the liturgical Psalter currently used by the (Orthodox) Church of Greece and published in 2021 by its official ecclesiastical organisation Apostoliki diakonia.2 I do not go back to the origins but rather, I go forward from antiquity to our time seeking to trace the genesis of the modern liturgical Psalter. Thus, the research data is the same, while the research direction is the opposite.

In the following paragraphs, we will see some results of my work with the Project catalogue during my sojourn in Göttingen. Namely, we are going to trace a textual variant from Ps 38:12c (LXX) from the earliest Greek manuscripts to the modern editions. The genesis of one textual variant is a step towards the history of the modern liturgical Psalter. Such steps are becoming possible thanks to the scientific instruments provided by the Project team and the research method I have been developing.

Once upon a time, there was Psalms 38:12c

In the Apostoliki diakonia edition of Ps 38:12c (LXX), we find:

πλὴν μάτην ταράσσεται πᾶς ἄνθρωπος.

But every man is troubled in vain.

The same text is found in the Psalmi cum Odis of Rahlfs. By contrast, in the MT, the verb is not present:3

אך הבל כל אדם

Surely, every person is vanity!

Nor is the verb present in the Hexaplaric fragments of Aquila and Symmachus;4 the verb is absent also from the Psalterium Romanum.5 In the Qumran texts, the verse is not extant.6

Thus, in this case, the modern liturgical text and the scientific reconstruction of the Old Greek do not differ. However, the apparatus of the Psalmi cum Odis shows that things are not so simple: the verb ταράσσεται is absent from two ancient witnesses (Alexandrinus and Sinaiticus), from the text of Sunnia und Fretela, and — crucial for us here — from the majority of Lucianic (that is Byzantine) texts.7 At this point, the question arises: When (and why) did ταράσσεται disappear from the Byzantine manuscript tradition, and when (and why) did it come back?

To answer this question, I consulted the textual witnesses from the earliest manuscripts to printed editions. It has become possible, thanks to the Project catalogue, which allows one to consult a vast number of digital reproductions of manuscripts without trekking from one library to another. However, since the Project has not yet been completed, I have also used both Verzeichnis editions.8

I selected the textual witnesses for the research according to the following principles:

-

For the first ten centuries, I consulted all the manuscripts mentioned in the Project catalogue and both Verzeichnisse, with few exceptions, where digital reproductions were not available.

-

From the 11th to 14th centuries, I consulted only five or six manuscripts per century.

-

For the 15th and 16th centuries, I consulted only those manuscripts whose digital reproductions were available in the Project catalogue. They constitute about one-third of the roughly four hundred manuscripts.

-

For the 17th to 21st centuries, I consulted some printed editions (indicated below by the sigla “Printed”).

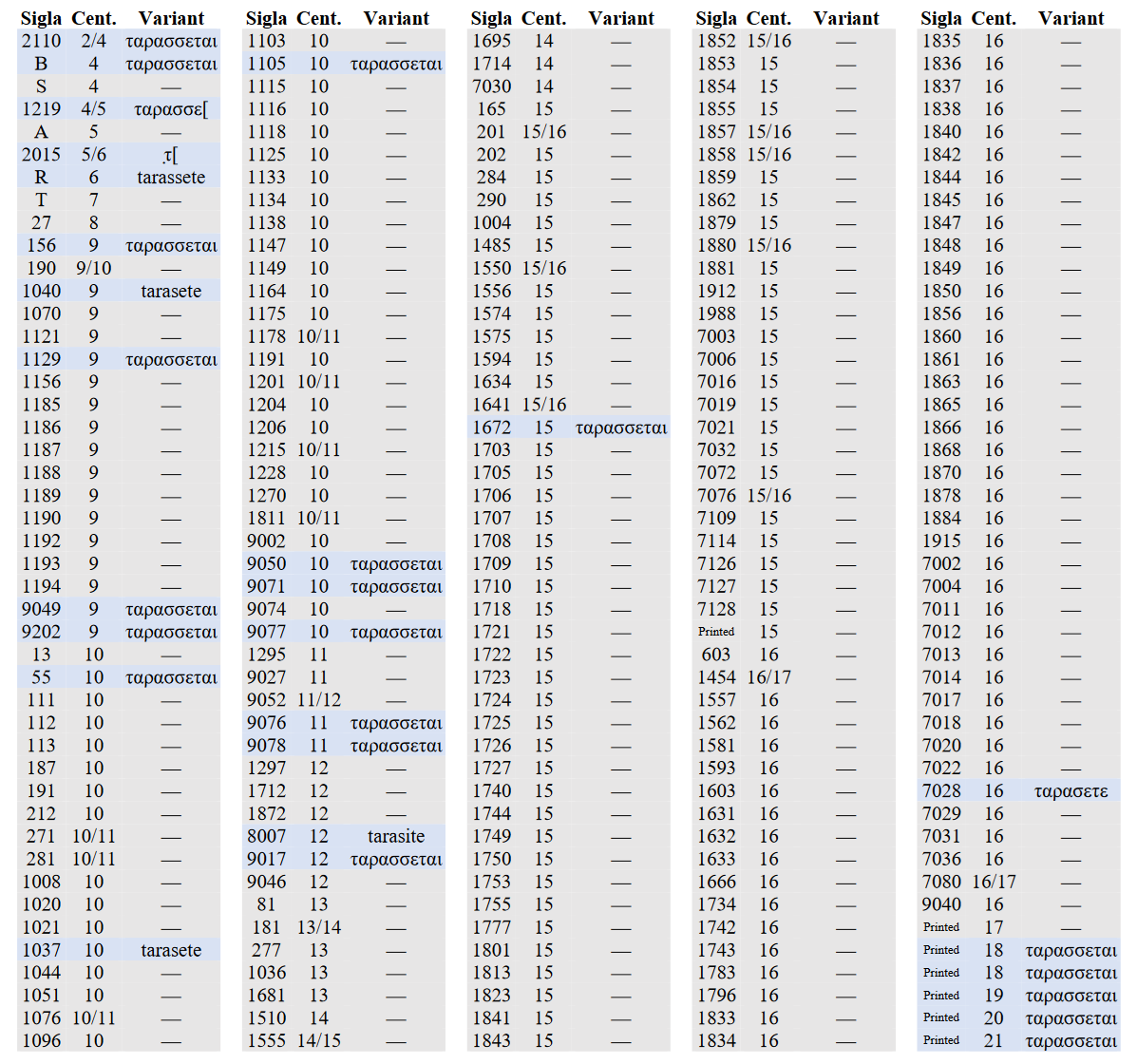

The results of the study are presented in the table below. The textual witnesses are given in chronological order; only the witnesses which contain Ps 38:12c are mentioned. The first column contains the manuscript sigla according to the Project catalogue (which employs an extended version of the sigla of Rahlfs). The second column contains the century, according to the description in the Project catalogue. The third column gives ταράσσεται (in original spelling) if present; otherwise, it gives a blank: “—”.

Figure 1: Presence/absence of ταράσσεται in Ps 38:12c in the Psalter manuscripts and printed texts from the 2nd to the 21st centuries.

Figure 1: Presence/absence of ταράσσεται in Ps 38:12c in the Psalter manuscripts and printed texts from the 2nd to the 21st centuries.

As the table demonstrates, the verb ταράσσεται occurs in the witnesses of the first five/six centuries (the evidence, however, is scarce). This is in agreement with the Psalmi cum Odis, which considers ταράσσεται as the Old Greek. By contrast, the verb is almost always absent from the manuscripts of the 9th to 16th centuries, as the sheer volume of evidence shows. Most of them must have been intended for prayer since they are divided into so-called doxai and kathismata.9 For the 11th to 14th centuries, I have checked only a few manuscripts; however, they seem to demonstrate the tendency. Finally, ταράσσεται surprisingly reappears in the printed editions from the 18th century on, including the modern liturgical text of the Church of Greece (the final entry in the table).

In the table, the manuscripts of the 9th to 16th centuries which contain the verb are not random: almost all of them were either produced in a Latin context or contain the commentary on the Psalms:

-

Manuscripts 156, 1040 and 1672 contain bilingual Greek–Latin Psalters.

-

In Manuscript 1129, there are translations of the titles and some initial words into Latin.

-

Manuscripts 1037 and 8007 are Psalteria Quadruplicia, which give three Latin versions by Jerome and the Greek text in four columns.

-

Manuscripts 9017, 9035, 9049, 9050, 9071, 9076, 9077 and 9078 contain the commentary of Theodoret of Cyrus.

-

Manuscript 9202 contains the commentary of Hesychius of Jerusalem.

Thus, the manuscripts containing ταράσσεται are somehow correlated either with the Latin world or with the patristic commentaries; this could indicate an academic rather than liturgical purpose. The reverse, however, is not true: the verb is absent from some manuscripts produced in a Latin milieu (e.g. 27, 277 and 1206) and from some commentaries (e.g. 1510, 9002, 9027 and 9046). The verb is present neither in the catena (e.g. 1270 and 1666) nor in other polyglot Psalters, such as Greek–Arabic ones (e.g. 1191 and 1714).

Among the manuscripts I analysed, I found only two exceptions from this tendency: Manuscripts 55 (10th c.) and 7028 (16th c.) actually have the verb. The former Psalter is the so-called “Leo Bible;” the latter seems to be a liturgical Psalter since it is divided into doxai and kathismata (e.g. f.15v). Given that in the 16th century, the verb in this verse seems to have disappeared entirely from the manuscripts, the reappearance of ταράσσεται in 7028 — a liturgical Psalter — is especially striking.

Results

Now we can try to respond to the question asked above and reconstruct “the story of life” of ταράσσεται in Ps 38:12c:

-

It must be part of the Old Greek.

-

It disappears in ca. the 7th–8th centuries.

-

It reappears in ca. the 17th–18th centuries.

Even if ταράσσεται is almost absent in the 9th–16th centuries, few witnesses conserved the verb: some Greek-Latin Psalters and some manuscripts with the Psalter interpretations. Thus, in the 9th–16th centuries, the absence of the verb was characteristic of Psalters in general, while its presence seems to be characteristic of some Psalters for scholarly use.

The reasons for the disappearance and reappearance of ταράσσεται remain mysterious. The verb may have been eliminated under the influence of the Hexapla of Origen to bring the text closer to its original Hebrew version. The verb may have been reintroduced under the influence of ancient witnesses like Vaticanus and Gallicanum to bring the text closer to its original Greek version.

Whatever reasons guided the redactors of Apostoliki diakonia, the version of Ps 38:12c used today for the liturgy by the Church of Greece does not correspond to the Byzantine tradition. It may exemplify how a scholarly version of the Psalter influences a liturgical one. It also means that the text used for the liturgy continues to develop and is still alive.

That was “the story of life” of Ps 38:12c. And the textual variant lived happily ever after…

* The author of this blog post is Filipp Porubaev – иеромонах Кирилл (Филипп Викторович Порубаев).

1 Alfred Rahlfs, ed., Psalmi cum Odis, 2nd ed., Septuaginta. Vetus Testamentum Graecum 10 (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1967). The first edition was published in 1931.↩︎

2 Το Ψαλτήριον τοῦ προφήτου καί Βασιλέως Δαυῒδ μετὰ τῶν ἐννέα ᾠδῶν (Ἀθήνα: Ἀποστολικὴ Διακονία τῆς Ἐκκλησίας τῆς Ἑλλάδος, 2021).↩︎

3 Cited according to Karl Elliger and Wilhelm Rudolph, eds., Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelstiftung, 1966).↩︎

4 See the Göttingen Hexapla Database; cf. Frederick Field, ed., Jobus–Malachias. Auctarium et indices, vol. 2 of Origenis Hexaplorum quae supersunt; sive Veterum interpretum Graecorum in totum Vetus Testamentum fragmenta (Oxford: Clarendon, 1875), 149.↩︎

5 Robert Weber, Le Psautier Romain et les autres anciens psautiers latins, CBLa 10 (Rome: Abbaye Saint-Jérôme, 1953), 85.↩︎

6 See Emanuel Tov, Revised Lists of the Texts from the Judaean Desert (Leiden: Brill, 2010).↩︎

7 For the Byzantine manuscripts see also Robert Holmes and James Parsons, eds., Vetus Testamentum Greacum cum variis lectionibus, vol. 3 (Oxford: Clarendon, 1823).↩︎

8 Alfred Rahlfs and Detlef Fraenkel, Verzeichnis der griechischen Handschriften des Alten Testaments. Die Übelieferung bis zum VIII. Jahrhundert, Septuaginta. Vetus Testamentum Graecum. Supplementum I,1 (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2004); Alfred Rahlfs, Verzeichnis der griechischen Handschriften des Alten Testaments, für das Septuaginta-Unternehmen, MSU 2 (Berlin: Weidmann, 1914).↩︎

9 On doxai and kathismata see Georgi R. Parpulov, Toward a History of Byzantine Psalters, ca. 850–1350 AD (Plovdiv, 2014), 54–55.↩︎

by Jonathan Groß and Peter Schreiner, January 20, 2026

by Bonifatia Gesche, December 23, 2025

by Matteo Domenico Varca, November 30, 2025

by Anna Kharanauli, October 31, 2025

by Jonathan Groß, September 26, 2025

by Felix Albrecht, August 31, 2025

by Vadim Wittkowsky, July 31, 2025