The Prayers of St Basil the Great in Psalters

Aleksandr Andreev

April 28, 2023

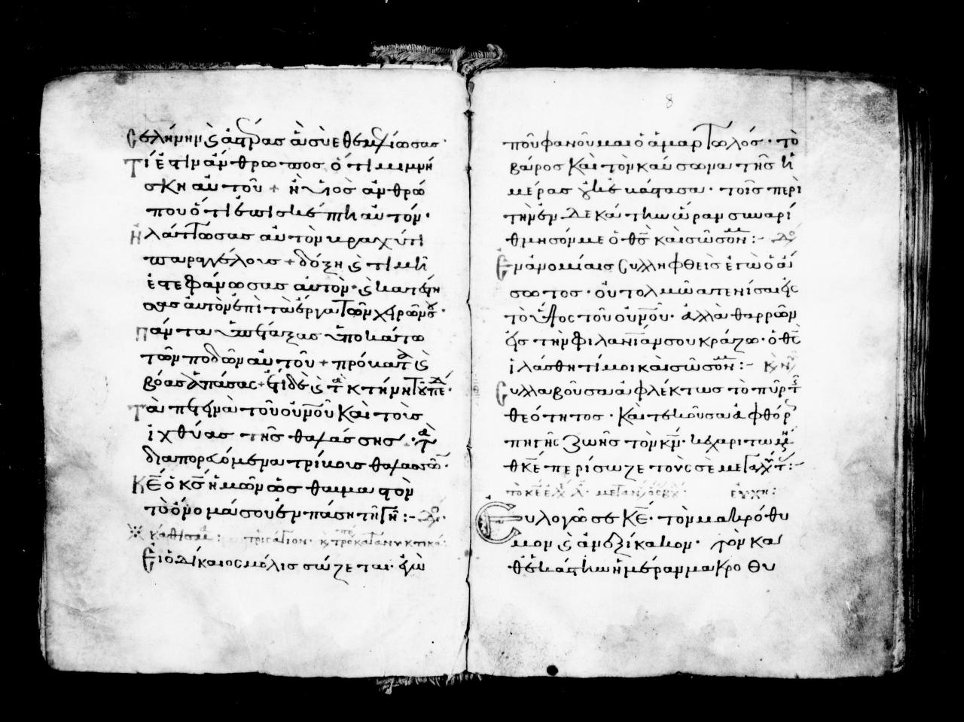

The Byzantine Psalter is more than just a scriptural book: it often contains, among other things, patristic texts, hymnography, and prayers. Psalters with prayers intended to be read following every cathisma (division of the Psalter into twenty sections) are of particular interest, because they were used for private devotion by monks or pious laypeople and thus reflect everyday Byzantine religious experience. These sources were first studied in detail by Georgi Parpulov in his dissertation[i]. The earliest manuscripts date to the 11th and 12th centuries: Sinai, Greek 40 (Ra 1815); Athos, Pantokratoros 43 (Ra 1530); Athos, Ibêrôn 22 (Ra 1019) and Harvard University, Houghton Library, Greek 3 (Ra 1271)[ii]. They contain a surprisingly similar collection of prayers, which is almost identical with the set of prayers found in a contemporaneous book for private devotion — the Horologion (Book of Hours) with a 24 hour cursus, for example, the late 11th century Bibliothèque nationale de France (BNF), Grec 331 (diktyon 49903)[iii] — at the 24 additional offices called “minor hours”. So these prayers were selected from various sources of monastic literature to be used for private devotion throughout the day. Starting in the 12th century the selection of prayers in Psalters changes significantly: new prayers are introduced from the Euchologion — which is the collection of liturgical prayers par excellence — and other sources and the prayers of the earliest sources gradually go out of use[iv].

Prayer after Cathisma 1 in Sinai, Greek 40 = Ra 1815 (f. 7v–8r). Photo credit: Library of Congress.

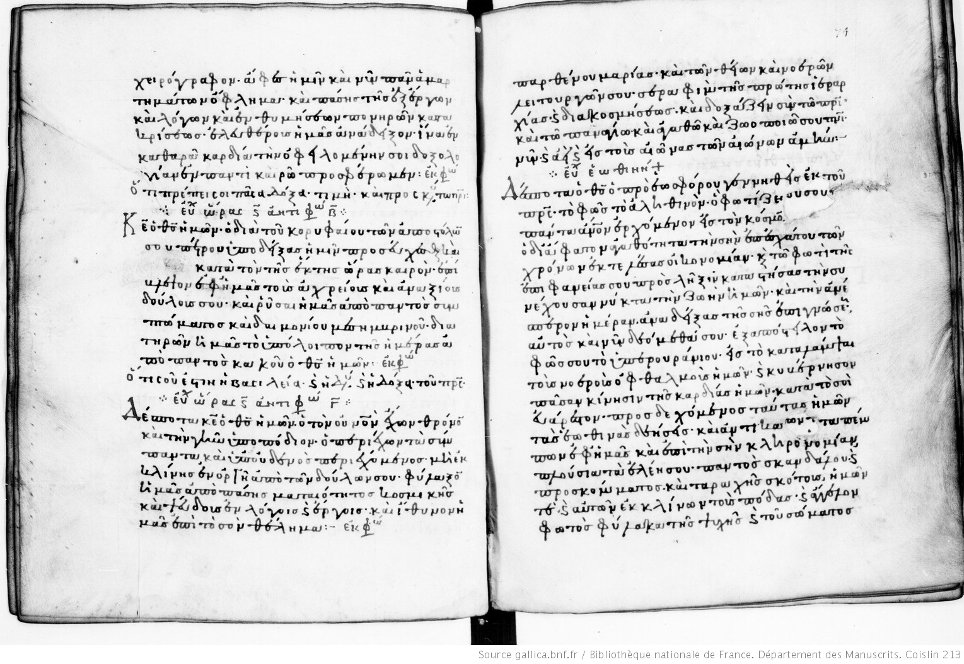

A curious set of prayers is found in a famous manuscript, the “Euchologion of Strategius” BNF, Coislin 213 (diktyon 49354, dated 1027), first studied by Aleksey Dmitrievsky, who provided a partial edition of its content[v]. In a series of papers Miguel Arranz identified it as an example of the Euchologion of the Great Church — that is, a patriarchal Euchologion reflecting the usage of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, even though it was intended to be used by the Priest Strategios[vi]. This set of prayers, ascribed to St. Basil the Great, is recorded in the manuscript on f. 74, following the prayers of the Constantinopolitan cathedral daily office[vii]. Due to a lacuna, only the ending of the first prayer has survived, but its full text has recently been identified — and edited — in the Horologion section of the above mentioned manuscript Houghton Library, Greek 3 (on f. 233v)[viii]. This set of prayers was first studied by James Duncan in a dissertation under the direction of Miguel Arranz, who identified their unusual endings and concluded that they are quite late and cannot be attributed to the fourth-century Cappadocian Father whose name they bear[ix].

Beginning of the Prayers of St Basil the Great in BNF, Coislin 213, f. 74r. Photo credit: Bibliothèque nationale de France.

The prayers are nine in total, one for each office of the monastic daily cycle, arranged from morning to night: at rising from sleep, for Matins, First Hour, Third Hour, Sixth Hour, Ninth Hour, Vespers, Compline, and Midnight. In its ending each prayer mentions one of the nine ranks of the heavenly powers according to the three-by-three classification of the De coelesti hierarchia (CPG 6600) of Dionysius the Pseudo-Areopagite[x] the Seraphim in the prayer at rising from sleep, the Cherubim in the prayer for Matins, the Thrones in the prayer for the First Hour, and so forth, concluding with the Angels in the prayer for Midnight. Clearly the cycle of prayers was put together in a monastic context and by someone with a devotion to the angels and an interest in the Corpus Areopagiticum. It is impossible to say for sure who this compiler was, but it was in the 11th century, too, that the Pseudo-Dionysian hierarchical model was further developed by the Byzantine theologian Nicetas Stethatus (beginning of the 11th century–between 1081 and 1092), abbot of the Studion Monastery, who in his own work on the hierarchy compares (rather artificially) the nine ranks of heavenly powers with nine ranks of the ecclesiastical hierarchy, equating the Seraphim with the patriarchs, the Cherubim with the metropolitans, and so forth[xi]. Could Studion also be the source for this curious cycle of Prayers of St Basil the Great?

If this were indeed the case, we would expect to find the same set of prayers in the Byzantine Horologia associated with the Studion Monastery. Alas, no Byzantine Horologion source contains this set of prayers in full. In addition to the prayer at rising from sleep, Houghton Library, Greek 3, which is Constantinopolitan, though not necessarily Studite, also contains the prayer for Matins, placed at the First Hour[xii], but not any of the other prayers. The 24-hour Horologia contain the largest number of these prayers, placed not at the devotional “minor hours” but at the canonical hours of the Byzantine daily cycle. For example, BNF, Grec 331 contains the prayers for First Hour, Sixth Hour, and Ninth Hour. In later Horologia these prayers are completely absent, so after the 12th century they must have entirely gone out of use[xiii].

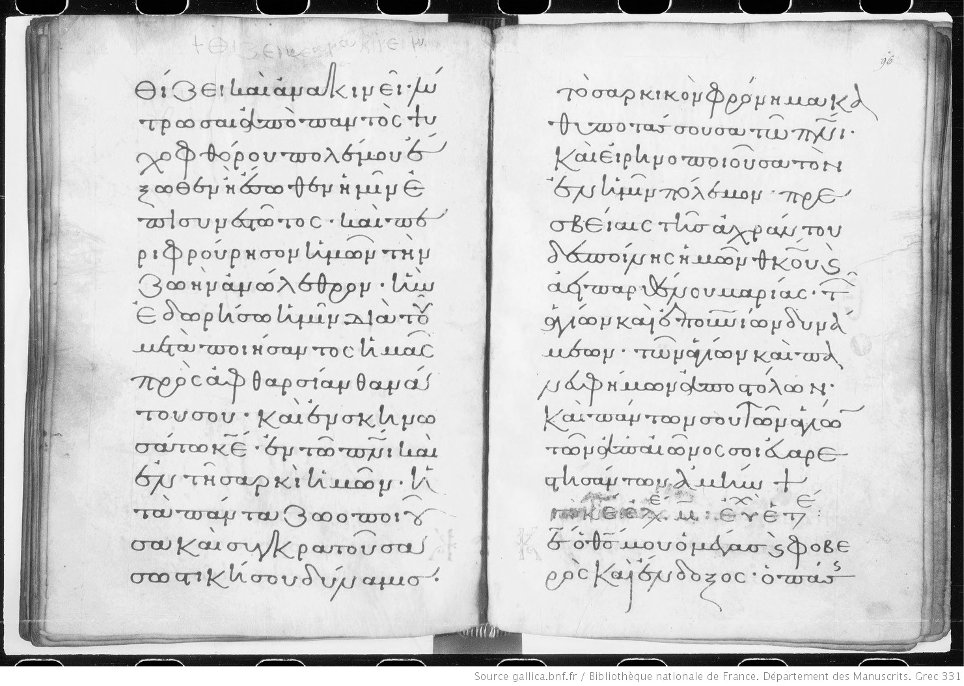

Ending of the prayer of the Ninth Hour in BNF, Grec 331, f. 95v–96r. Photo credit: Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Curiously, the endings of these prayers in the 24-hour Horologia do not mention the heavenly hierarchy, rather containing a typical generic listing of the saints[xiv]. For example, here is the ending of the prayer at Ninth Hour:

|

Paris, BNF, Coislin 213, f. 76r |

Paris, BNF, Grec 331, f. 96r |

|

<…> καὶ εἰρηνοποιοῦσα τὸν ἐν ἡμῖν πόλεμον, πρεσβείαις τῆς ἀχράντου δεσποίνης ἡμῶν Θεοτόκου καὶ ἀειπαρθένου Μαρίας, καὶ τῶν ἀΰλων καὶ νοερῶν λειτουργῶν σου, τῶν θείων ἐξουσιῶν τῆς δευτέρας καὶ μέσης ἱεραρχίας καὶ διακοσμήσεως, ἵνα ἐν τῇ σῇ δοξάζωμεν εἰρήνῃ τὸ πανάγιον ὄνομά σου σὺν τῷ Πατρὶ καὶ τῷ παναγίῳ καὶ ἀγαθῷ καὶ ζωοποιῷ σου Πνεύματι |

<…> καὶ εἰρηνοποιοῦσα τὸν ἐν ἡμῖν πόλεμον, πρεσβείαις τῆς ἀχράντου δεσποίνης ἡμῶν, Θεοτόκου καὶ ἀειπαρθένου Μαρίας, τῶν ἁγίων καὶ ἐπουρανίων δυνάμεων, τῶν ἁγίων καὶ πανευφήμων ἀποστόλων καὶ πᾶντων σου τῶν ἁγίων, τῶν απ᾿ αἰῶνος σοι εὐαρεστησάντων, ἀμήν. |

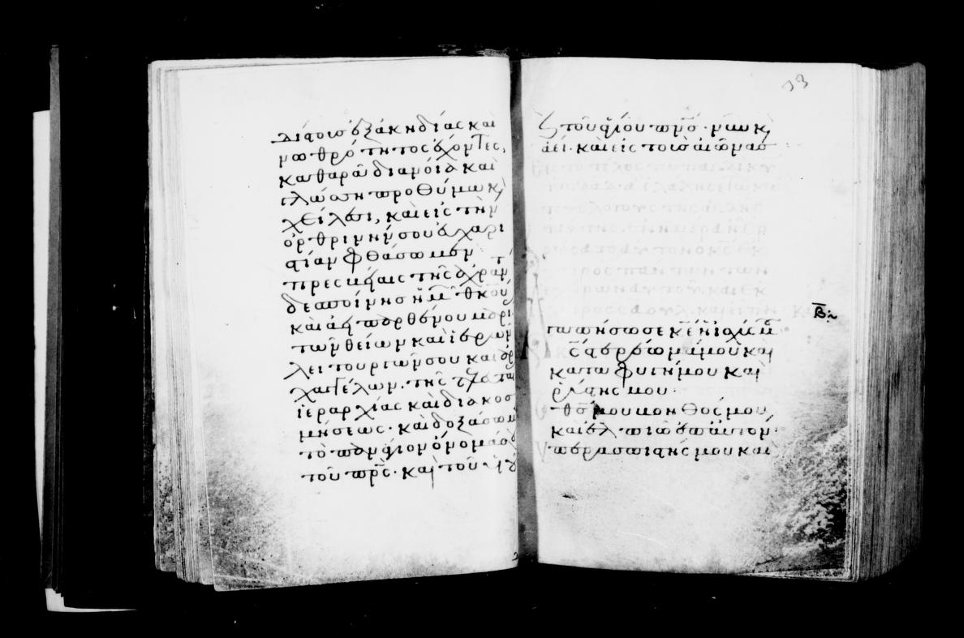

That some of the prayers occur at the canonical hours in the 24-hour Horologia is a good indication that they indeed must have functioned as prayers of the daily cycle in some milieu in the Byzantine capital. But just which milieu was this? And which version of the prayers is the earlier — the one with the Pseudo-Dionysian hierarchy or the one without it? Since the prayers occur at the canonical hours and not at the devotional minor hours, they are not found in the earliest Psalters with prayers after each cathisma. However, they do occur in some of the later Psalters, which contain a very diverse selection of prayers. Here we observe another curiosity: those prayers that are recorded in the 24-hour Horologia occur in the Psalters without the endings mentioning the Dionysian hierarchy, just as in the Horologia, while those prayers that do not occur in the 24-hour Horologia preserve in the Psalters mention of the heavenly hierarchy, just as in the Euchologion of Strategius. For example, here are the endings of two prayers as they are found in the Psalter Sinai, Greek 46 (diktyon 58421; beginning of the 14th century).

|

Sinai, Greek 46, f. 90r After Cathisma 5 |

Paris, BNF, Grec 331, f. 96r At the Ninth Hour |

|

<…> καὶ εἰρηνοποιοῦσα τὸν ἐν ἡμῖν πόλεμον, δυνάμει τοῦ τιμίου καὶ ζωοποιοῦ σου σταυροῦ, πρεσβείαις τῆς ἀχράντου καὶ ὑπερευλογημένης σου μητρὸς καὶ πάντων τῶν ἁγίων τῶν ἀπ᾿ αἰῶνος σοι εὐαρεστησάντων ὅτι σοι ἡ δόξα καὶ ἡ τιμὴ παρὰ πᾶσης κτίσεως ἐπουρανίου καὶ ἐπιγείου ἐποφείλεται. |

<…> καὶ εἰρηνοποιοῦσα τὸν ἐν ἡμῖν πόλεμον,

πρεσβείαις τῆς ἀχράντου δεσποίνης ἡμῶν, Θεοτόκου καὶ ἀειπαρθένου Μαρίας, τῶν ἁγίων καὶ ἐπουρανίων δυνάμεων, τῶν ἁγίων καὶ πανευφήμων ἀποστόλων καὶ πᾶντων σου τῶν ἁγίων, τῶν απ᾿ αἰῶνος σοι εὐαρεστησάντων, ἀμήν. |

|

Sinai, Greek 46, f. 32v After Cathisma 2 |

Paris, BNF, Coislin 213, f. 76r At Compline |

|

<…> καθαρᾷ διανοίᾳ καὶ γλώσσῃ προθύμῳ, καὶ χείλεσι καὶ εἰς τὴν ὀρθρινήν σου εὐχαριστίαν φθάσωμεν, πρεσβείαις τῆς ἀχράντου δεσποίνης ἡμῶν Θεοτόκου καὶ ἀειπαρθένου Μαρίας, τῶν θείων καὶ ἱερῶν λειτουργῶν σου καὶ ἀρχαγγέλων τῆς τελευταίας ἱεραρχίας καὶ διακοσμήσεως, καὶ δοξάζωμεν τὸ πανάγιον ὄνομά σου τοῦ Πατρὸς καὶ τοῦ Υἱοῦ καὶ τοῦ ἁγίου Πνεύματος νῦν καὶ ἀεί καὶ εἰς τοὺς αἰῷνας. |

<…> ἵνα πεφωτισμένῃ διανοίᾳ καὶ γλώσσῃ προθύμῳ, καὶ χείλεσιν εἰς τὴν σὴν παραστῶμεν εὐχαριστίαν, πρεσβείαις τῆς ἀχράντου δεσποίνης ἡμῶν Θεοτόκου καὶ ἀειπαρθένου Μαρίας, τῶν θείων καὶ νοερῶν λειτουργῶν σου καὶ ἀρχαγγέλων τῆς τελευταίας ἱεραρχίας καὶ διακοσμήσεως, καὶ δοξάζωμεν τὸ πανάγιον ὄνομά σου τοῦ Πατρὸς καὶ τοῦ Υἱοῦ καὶ τοῦ ἁγίου Πνεύματος νῦν καὶ ἀεί. |

Although the text of the prayer of Compline as found in Sinai, Greek 46 after Cathisma 2 differs substantially from the text in the Euchologion of Strategius, the ending is preserved almost verbatim and the reference to the Dionysian heavenly hierarchy is apparent. It could be the case that in these later Psalters some of the prayers were copied from Euchologia and others from Horologia, but we are still no closer to discovering their original function and milieu.

Ending of the prayer following Cathisma 2 in Sinai, Greek 46 = Ra 1817, f. 32v–33r. Photo credit: Library of Congress.

An important key to solving this puzzle comes from a quite unexpected source: the early East Slavic Horologion (Chasoslovets), attested in three sources now preserved at the National Library of Russia in St. Petersburg: Q.п.I.57 (first half of the 13th century) and Sof. 1052 and O.п.I.2 (both from the second half of the 14th century)[xv]. These Horologia contain the services of the daily cycle in precisely the arrangement of the prayers of St Basil the Great: cock-crow (rising from sleep); Matins; First, Third, Sixth, and Ninth Hours; Vespers; Compline; and Midnight. Since they contain offices for private prayer — in addition to cock-crow and Midnight, these include a service of Night Hours as well as Mid-Hours for each Hour, which were originally private devotions that later became communal — they must reflect the usage of some monastic community.

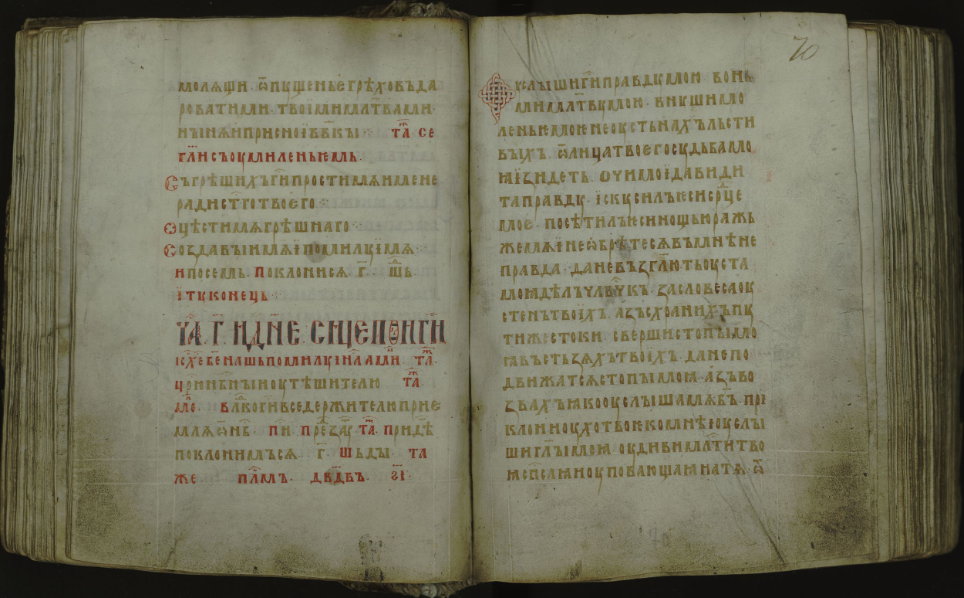

The beginning of Third Hour in Sof. 1052, f. 69v–70r. Photo credit: National Library of Russia.

Of these sources, Sof. 1052 contains the full set of prayers of St Basil the Great. The prayer for rising from sleep is placed at the office of cock-crow; the second prayer — at Matins; the prayers for the Hours — at the Mid-Hours of First, Third, Sixth, and Ninth Hour; and the prayers for Vespers, Compline, and Midnight — at their respective locations. Unfortunately, O.п.I.2 is now missing both its beginning and ending, but it probably also contained the full set of prayers, since the arrangement of the prayers in the portion of this manuscript that has survived matches that of Sof. 1052. In Q.п.I.57, which is the earliest source, the prayers of the Hours are placed at the Hours themselves, rather than at the Mid-Hours, and the prayers for Vespers and Midnight Office are absent, with different prayers taking their place. Other than the Euchologion of Strategius, Sof. 1052 is our only other source for the complete set of these prayers, albeit in translation into Slavonic. Curiously, the prayers in this source are recorded also with the endings referring to the Dionysian heavenly hierarchy, as we can see from the text of, again, the prayer of the Ninth Hour:

What can this tell us about the prayers’ original function? While our surviving Slavonic Horologion manuscripts date from the 13th century and later, the book must have been translated earlier. The three surviving sources have many textual discrepancies that must have accumulated over one or two centuries of copying. Furthermore, by the 13th century, the Byzantines already used an Horologion of a different type, with a different structure of private offices and a different selection of prayers at each office. Therefore, our 13th and 14th century sources must attest to an Horologion translated into Slavonic probably some time in the late 11th or early 12th century. We know that at some point between 1062 and 1074, the Typicon of Alexis the Studite, which reflects the liturgical practice of the Monastery of the Dormition of the Theotokos in Constantinople, was translated into Slavonic for the Monastery of the Caves in Kiev. The Chasoslovets does not correspond to this Studite-Alexis Typicon exactly, reflecting a somewhat later stage in the development of the Hours and Mid-Hours. Nonetheless, we have here one further clue connecting the Prayers of St Basil the Great with the Studion Monastery, since, like Nicetas Stethatus, Alexis the Studite had been the abbot there prior to his election to the patriarchate in 1025[xvi].

What, however, was the original function of these prayers? In Sof. 1025 they occur at the Mid-Hours, but in Q.п.I.57 — at the Hours, and this latter position must be the earlier one, since the Mid-Hours only emerge in Constantinople in the second half of the 11th century. Some more clues to answering this question may come from studying the evolution of the Slavonic text of these prayers, which is the topic of an ongoing project, the results of which, we hope, will soon be published in a joint paper with Tatiana Afanasyeva. Meanwhile, it is curious to see already how peripheral sources — this time those from Kievan Rus — help us understand the religious experience of the Byzantine capital, providing important clues for the history of the prayers in the Byzantine Psalter and Horologion.

[i] G. R. Parpulov, Toward a History of Byzantine Psalters ca. 850–1350 AD (Plovdiv, 2014), 103–116.

[ii] This manuscript has been edited: J. Anderson and S. Parenti, A Byzantine Monastic Office, 1105 A.D. (Washington, 2016).

[iii] These were studied by the Greek liturgist Ἰ. Μ. Φουντούλης, Ἡ Εἰκοσιτετράωρος Ἀκοίμητος Δοξολογία (Ἀθῆναι, 1963).

[iv] This is clearly seen in the table presented in Parpulov, Toward a History of Byzantine Psalters, Appendix C3.

[v] A. A. Dmitrievsky, Описание литургических рукописей, хранящихся в библиотеках православного Востока. Т. 2: Εὐχολόγια (Kiev, 1901), 993–1052.

[vi] M. Arranz, “Les Sacrements de l’ancien Euchologe constantinopolitan (1),” OCP 48 (1982): 284–335, at 309–314.

[vii] Edited by Dmitrievsky, Описание литургических рукописей, 1004–1008.

[viii] Anderson and Parenti, A Byzantine Monastic Office, 80–82.

[ix] J. Duncan, Coislin 213: Euchologe de la Grande Église. Dissertatio ad Lauream (Rome, 1983), cxxv–cxxxix.

[x] De coelesti hierarchia VI.2, edited in Corpus Dionysiacum, II: Pseudo-Dionysius Areopagita, De coelesti hierarchia, De ecclesiastica hierarchia, De mystica theologia, Epistulae, 2 überarbeitete Auflage, herausg. von G. Heil und A. M. Ritter (Berlin-Boston 2012) (=Patristische Texte und Studien, 67), 26–27.

[xi] On the Hierarchy 22, edited in Nicétas Stéthatos, Opuscules et Lettres, introd., texte critique, trad. et notes par J. Darrouzès (Paris, 1961) (=Sources Chrétiennes 81), 326.

[xii] Anderson and Parenti, A Byzantine Monastic Office, 112.

[xiii] This is evident from the table presented in Parpulov, Toward a History of Byzantine Psalters, Appendix C4.

[xiv] This observation was first made by Tatiana Afanasyeva.

[xv] There is, so far, no study of the Chasoslovets in print, but for an introduction to the early East Slavic Horologion see Ye. E. Sliva, “Часословы студийской традиции в славянских списках XIII–XV вв.,” Труды Отдела древнерусской литературы 51 (1999): 91–106.

[xvi] On Patriarch Alexios the Studite and his Typicon see A. M. Pentkovsky, Типикон патриарха Алексия Студита в Византии и на Руси (Moscow, 2001).

by Jonathan Groß and Peter Schreiner, January 20, 2026

by Bonifatia Gesche, December 23, 2025

by Matteo Domenico Varca, November 30, 2025

by Anna Kharanauli, October 31, 2025

by Jonathan Groß, September 26, 2025

by Felix Albrecht, August 31, 2025

by Vadim Wittkowsky, July 31, 2025