Contributions towards a Critical Edition of Aquila and Symmachus in the Psalter

Kyle Young

April 30, 2025

Before commencing with a large-scale comparison of Aquila, Targum Onqelos, et al. in my in-progress thesis,1 I sought the most complete contiguous texts of the Three available. In the case of Aquila and Symmachus, this naturally led me to the Hexapla Psalter palimpsests, Ra 1098 and Ra 2005.2 Taylor published the editio princeps of Ra 2005 in 1900 and Mercati that of Ra 1098 in 1958.3 Beyond these, an appendix in Busto Saiz’ published dissertation establishes a critical edition of Symmachus in the Psalter;4 he emends the texts of Ra 1098 and Ra 2005 using the likes of Field and Mercati’s «Osservazioni».5 Much more recently, Carrera completed a dissertation providing a new, diplomatic edition of Ra 1098 based on enhanced technological imaging.6 Whereas Mercati’s edition presents a slightly edited version of Ra 1098, somewhat in the vein of Rahlfs’ Septuaginta, Carrera transcribes the text as is without editorial corrections.7 He informs us that he will at least briefly discuss all differences between himself and Mercati.8 Thus, for Aquila, one only has Taylor’s edition in the case of Ra 2005, but one must choose between Mercati and Carrera for Ra 1098. In the case of Symmachus, one can begin with Mercati or Carrera for Ra 1098 and Taylor for Ra 2005 or, more simply, use Busto Saiz for both Ra 1098 and 2005. The scholar who does not start from scratch still has many decisions to sort through!

In the process of comparing every line of Aquila and Symmachus in the relevant passages provided by Field, Taylor, Mercati, Busto Saiz, and Carrera, I eventually opted to take the excellent work of Busto Saiz as my point of departure for Symmachus9 plus Mercati and Taylor for Aquila. Accordingly, my goal is to present improvements in the readings of Aquila and Symmachus that I have made to these starting points. Unlike the ongoing labours of the “Editio critica maior des griechischen Psalters” and Hexapla Project, I collect no new readings; I am largely at the mercy of Mercati’s «Osservazioni», which surpass Field in scope and specificity. Further, I am not comprehensively representing all readings of Aquila and Symmachus available: I only discuss what I believe to be the preferable readings of Aquila and Symmachus for the passages attested by Ra 1098 and Ra 2005 if I think the original readings differ from Mercati and Taylor’s editions of Aquila or Busto Saiz’ edition of Symmachus. By implication, my silence is meaningful – it indicates my judgment that my base texts are secure against whatever alternatives are presently available to scholars as per the above resources.

Conventions and Qualifications

The presentation of my critical work below follows a modified format of the Hexapla Project that Meade’s edition of Job 22–42 pioneers.10 I do not label my discussions “Notes”. My observations on translation technique are kept to a minimum, except where absolutely necessary for reconstruction. The rightward arrow (→) represents “translated as.” The Hebrew text (“HT”) comes from Accordance’s “Hebrew Masoretic Text with Westminster Hebrew Morphology (HMT-W4),” version 2.2, which I believe is preferable to BHS. In the case of the “LXX,” the text comes from Rahlfs’ Psalmi cum Odis,11 with all its accompanying contingencies.12 The versification follows the Heb. first, followed by Grk. in parentheses.

To minimise lengthy references, the last names of Field, Taylor, Mercati, Busto Saiz, and Carrera entail their editions.13 I refer to Mercati’s second volume of Psalterii hexapli reliquiae as the «Osservazioni»14 and, given its eminent value, I occasionally make reference to the CTAT volume on the Psalter as “Barthélemy.”15 I do not cite page numbers when citing the texts of the editions, as the chapter and verse adequately entail the location. I do, however, always cite page numbers in parentheses for the «Osservazioni» and Barthélemy as well as when Mercati has footnotes in his edition (i.e., not «Osservazioni»)16 or when I am citing from Carrera’s commentary. For convenience, I state that Ra 1098 gives attributions to αʹ or σʹ, while this is only implicit by columnar sequence. The sigla for the manuscripts follow Rahlfs numbers (where assigned) rather than, e.g., text-group or institutional shelf marks.17

The presentation of my work always encompasses Field, Mercati, Busto Saiz, Carrera, the «Osservazioni», and Barthélemy. As I am providing no new manuscript readings, the «Osservazioni» are particularly crucial because they give more detailed manuscript information than Field was able to provide.18 That said, only Field habitually quotes the Syh readings, from whom they invariably come. While in the notes I discuss salient differences in the readings revolving around dubious letters, implicit information, iota adscript versus subscript, etc., in the critical representation I omit such details. More significant emendations will become apparent in my comments.

There are certain verses of Ra 1098 where the text represents obvious scribal errors that do not warrant a full collation of all manuscript evidence. On the one hand, the scribe of Ra 1098 in several instances reveals dittography. Verse 28(27):7 is repeated in its entirety; I omit the second instance.19 Additionally, three minor instances of dittography occur in the column of Aquila. Mercati corrects only the second but I correct them all here rather than in fuller detail below: thus, read καὶ οὐκ εὔφρανας instead of καὶ οὐ καὶ εὔφρανας in 30(29):2b;20 οὐκ ὄψεται instead of οὐκ ὄψεται οὐκ ὄψετ(αι)21 in 49(48):10b;22 and καὶ ἄν(θρωπ)ος instead of (καὶ) ἄν(θρωπ)ος καὶ ἄν(θρωπ)ος in 49(48):13a. On the other hand, the scribe omits an entire verse across all columns in 18(17):3423 and 30(29):3; two lines across all columns in 46(45):11b; and one line across all columns in 18(17):29a. I have not undertaken to restore any of these. Beyond these scribal errors of Ra 1098, Mercati also has typos for Aquila which I correct here: in 35(34):19, read ψεύδ̣ους rather than φεύδ̣ους; in 49(48):11, read ἀσύνετος and εὐπορίαν instead of ασύνετος and ἐυπορίαν, respectively.24

Provisional Critical Improvements to Aquila and Symmachus

18(17):34b Aq

The lacuna in Ra 1098 for ὑψώματά μου comes at the top line of the relevant folio, which is broken off across all columns in Ra 1098 (see Carrera, 189–90). Mercati represents traces of one acute accent (thus, καὶ ἐπι τὰ ⁎ ⁎ ⁎ ⁎ ⁎ ⁎́ ⁎ ⁎ στήσει με·). Both manuscripts attest the added article, which should be kept despite the doubts expressed in the «Osservazioni» (11).

18(17):36a Sym

Faithfully following Field, Busto Saiz gives the text of Symmachus as σωτερίας [sic] σου and states in his apparatus, “σου 1ᵒ] F(οἱ πάντες); μου O.39; ךָ- TH.” Field presents the corrupted attributions as he himself received them: “Οʹ. ὑπερασπισμὸν σωτηρίας μου. Οἱ πάντες· ὑπερασπισμὸν σωτηρίας σου. Sʹ [i.e., ϛʹ]. ὑπερασπιστῆρα τοῦ σωτῆρός σου.” The «Osservazioni» (12) suggest that the pertinent “Vat.” manuscript, Ra 1175, gives only a partial scholion to highlight the markedness of the lexeme ὑπερασπισμός. While other attributions require disentangling,25 the reading of Symmachus is secure.

30(29):6d Aq

Mercati (23 and n.) reconstructs ⟨αἶνος.⟩ and comments that the circumflex is clear, while Carrera (223) transcribes α̣ἶ̣ν̣ ̣ ̣ and supplements with photos. We follow the text as both 264 and 1098 record it with πρωῒ, though the «Osservazioni» (77) suggest Aquila more likely translated πρωΐα.

30(29):10d Aq

As all the other columns of Ra 1098 translate -הֲ … -הֲ as μὴ … ἤ, one can too easily conceive of the copyist overlooking the nu and writing ἤ like for the others. Thus, follow Ra 264 (so «Osservazioni», 82).

31(30):20a Aq

The beginning of this folio of Ra 1098 does not preserve the first word of the verse. The several witnesses besides Ra 1098 that lump the attributions of Aquila and Symmachus together continue beyond the portions excerpted above, revealing similarities plus overlooked differences. Nevertheless, Aquila and Symmachus in all likelihood translated this first line identically, except for the latter adding the article which the former did not (see «Osservazioni», 126).

31(30):21b Sym

Ra 1098 leaves the ending of ἀντιλογι- implicit. Without further comment, Mercati and Carrera both transcribe ἀντιλογι(ῶν) as a plural, matching the Secunda’s μριβη, and Busto Saiz follows suit with ἀντιλογιῶν. This is entirely unexpected. The previous line of Symmachus has the singular παραδειγματισμοῦ for HT’s plural מֵרֻכְסֵי, suggesting Symmachus (like οἱ οʹ εʹ) and the Vorlage or reading tradition of the Secunda both harmonised in opposite directions: the Secunda with the plural μριβη (hence מֵרִיבֵי) to match מֵרֻכְסֵי, and Symmachus (sim. οἱ οʹ εʹ) with the singular παραδειγματισμοῦ (hence מֵרֹכֶס) to match מֵרִיב. Thus, read ἀντιλογίας.

32(31):9b–c Aq

Rahlfs 264 does not conflate Aquila and Symmachus in the way one would expect from Field (see «Osservazioni», 168–70).26 The Syh does indeed combine them, as if translating (in my judgment) διὰ κημοῦ καὶ χαλινοῦ περιθέσεως τοῦ ἐπιστρέψαι οὐ μὴ ἐγγίσῃ πρὸς σέ. The «Osservazioni» (170) fittingly suggest an initial τοῦ fell out due to haplography with the preceding αὐτοῦ. We can represent this as a retroversion from Syh’s prepositional clitic rather than reconstructing it in brackets. Finally, the reading of Ra 1098 is represented above as ἐπιστρέψαι instead of Mercati’s ε⁎⁎επιστρέψαι because the “prefix ‘εἰσ-’ is not visible” according to Carrera (265).27

The «Osservazioni» (170–71) prefer περιστρέψαι of Ra 264 over the idea of Aquila translating the Heb. hapax legomenon לבלום → ἐπιστρέφειν, as Aquila regularly translates לשׁוב → ἐπιστρέφειν but only uses περιστρέφεσθαι28 once in translating the hitpael להתהפך (Job 37:12). But if Aquila indeed never uses the same Greek word to translate two different Hebrew words, then even using περιστρέφεσθαι once elsewhere is too much; we would have to conjecture that Aquila here used a third, unattested verb.29 The best solution is the simplest: an original ἐπιστρέψαι was likely changed to περι- due to influence from Symmachus’ περιθέσεως.

32(31):11b Aq

In what could be a telling indicator of dependence, Ra 264 gives two quotations of Aquila: the first follows Ra 1098 (αἰνοποιεῖτε) and the second Ra 1175 (αἰνοποιήσατε).31 The previous two verbs of Aquila in 32(31):11a are εὐφράνθητε and ἀγαλλιᾶσθε; while the first is clearly subjunctive, the second is imperative but could be parsed as subjunctive. Plausibly, αἰνοποιήσατε originated through a scribe interpreting ἀγαλλιᾶσθε as subjunctive and then modifying ἀγαλλιᾶσθε to match.

The primary reason for including this stichos is that Mercati transcribes the final word as καρδίαν, which Carrera modifies to καρδίαι before noting, “Contra Mercati, this is a iota adscript, not a nu.” (266)32 There is, therefore, no discrepancy at all for the case ending of καρδία. Accordingly, we also do not need to dismiss – as the «Osservazioni» (175 n. 25) recommend – the attribution to Aquila (= Theodotion), καρδίᾳ, in Ps 94(93):15.

35(34):13a Aq

Mercati and Carrera alike transcribe Aquila’s translation of בַּחֲלוֹתָם as ἐν ἀρρωστίαις αὐτ(ῶν). The scribe of Ra 1098 seems to have been distracted both with the lines of Symmachus – on which see Mercati (55 n.; also «Osservazioni», 205–06), whom Busto Saiz follows in his edition – and of Aquila. Though the page from which the scribe copied likely had ἀρρωστίαι, the scribe unintentionally slipped in a sigma from the original line of Symmachus. In this instance, Syh ignores the difference between the number of Aquila and Symmachus. As per the «Osservazioni» (206–07), we follow the singular reading.

35(34):14b Aq

Mercati transcribes κα ⁎ ⁎ ⁎ ⁎ ⁎ and proposes ‘possibly κατέκυψα.’ (55 n.) Carrera transcribes κατέ̣κ̣υψα and then comments: “κατέ̣[κ]υψα—The first three letters are visible as well as the last three. The middle kappa is completely blocked.” (283)33 Thus, we read κατέ⟨κ⟩υψα.

35(34):15 Aq

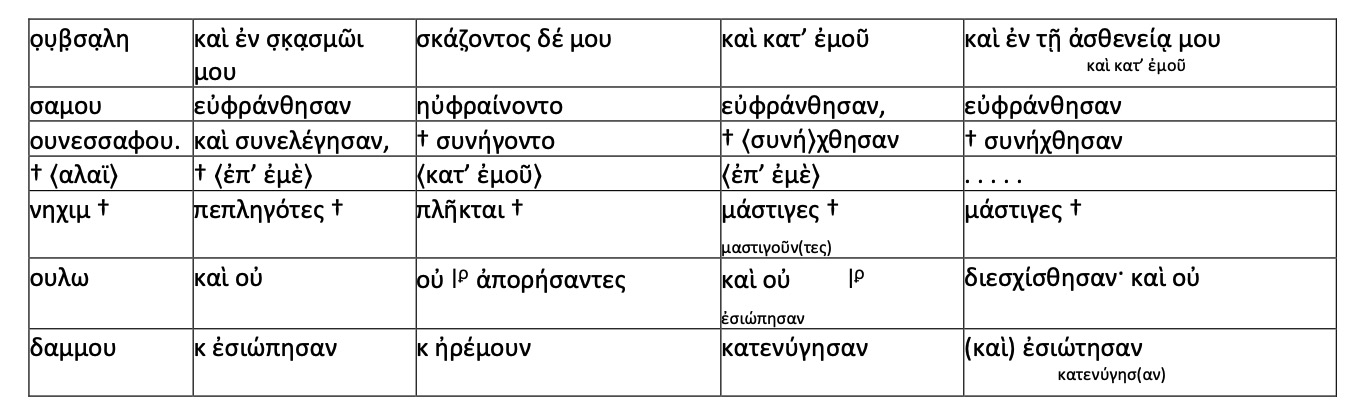

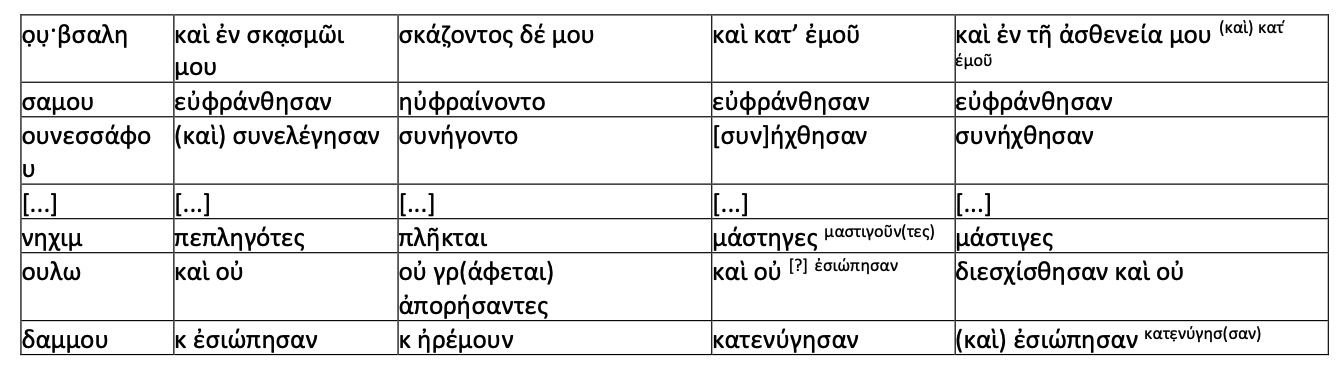

The verbal repetition of וְנֶאֱסָפוּ נֶאֶסְפוּ and the similarities between וְלֹא יָדַעְתִּי and וְלֹא־דָמּוּ invite fluctuation. 4QPsᵃ (4Q83) indeed reveals variation with the former, lacking וְנֶאֱסָפוּ and עָלַי by reading שמחו נ̊אס̊פ̇ו̇ ◦[ולא ידעתי.35 With Ra 1098, the scribe or his source seemingly passes over the former lines we would expect from וְלֹא יָדַעְתִּי קָֽרְעוּ: the Secunda skips from νηχιμ (= נֵכִים) to ουλω δαμμου (= וְלֹא־דָמּוּ). The scribe thus registers surprise via the notation γρ(άφεται) (Mercati = ❘ϼ) that Symmachus et al. has a “plus.”36 The entire verse as Mercati and Carrera transcribe it stands as follows:

Table 1: Mercati’s transcription of Ps 35(34):15 according to Ra 109837

Table 2: Carrera’s transcription of Ps 35(34):15 according to Ra 109838

We partially follow the reconstruction that the «Osservazioni» (211–14, esp. 212) suggest of reading ⟨συνελέγησαν ἐπ’ ἐμέ⟩ for Aquila. The corrupted line of Ra 1098 has sufficient space to reconstruct the line for נֶאֶסְפוּ or עָלַי (cf. Carrera, 284), and we accept restoring ⟨ἐπ’ ἐμέ⟩ (= עָלַי) for Aquila. However, it seems entirely plausible that Aquila’s Vorlage lacked נֶאֶסְפוּ (thus Kennicott MS 147,39 similar to 4QPsᵃ), so we do not accept the suggested restoration of ⟨συνελέγησαν⟩.

Our emending ᾔδειν to ⟨ἔγνων⟩ follows the «Osservazioni» (214 and n. 27), based on Ps 34(33):8, which has ιαδαθ for the Secunda and εγνως for Aquila.

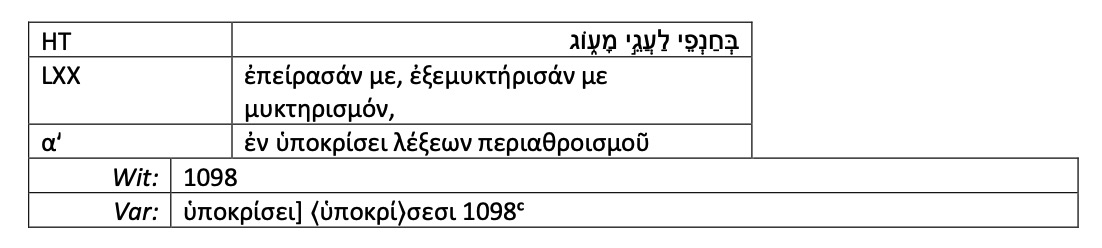

35(34):16a Aq

The line in Ra 1098 reads ἐν ὑποκρίσει σεσι. Mercati (55 n.) insists we should ‘certainly read’ ἐν ὑποκρίσεσι, which Barthélemy (207) follows. As the parallel lines of σʹ and εʹ have ἐν ὑποκρίσει, the «Osservazioni» (217) are quick to conclude that Aquila actually had σεσι and that the scribe mistakenly copied the singular from the others: the original reading must have been plural because Aquila was pedantic and a Christian scribe could not have known that the Heb. word being translated was plural.

Mercati’s explanation is the obvious answer yet certain facts weigh against it. First, it does not mesh well with the scribal practices of Ra 1098, attested in dozens of cases where the scribe made corrections.40 The pervasive way in which he corrected are (1) by writing over incorrect letters; (2) by erasing incorrect letters before rewriting them; or (3) by supralinear corrections (see Carrera, 58–59). In only one instance is there a sublinear correction (see Carrera, 318).41 Were the scribe “correcting” the text by his typical modus operandi, we would expect him to expand the final iota of ὑποκρίσει to make sigma before adding another iota (thus, ὑποκρίσεσι) or to write the correction supralinearly. Writing to the right is the typical way of presenting variant versions, not corrections. Second, no a priori reason exists why a Christian scribe could not know enough Heb. to “correct” Aquila. All that would be required is someone observant enough (1) to discern inductively the correlation between transcriptions in the Secunda and number, as with the plural form βαάνφη here, and (2) to expect that Aquila “should” have translated plural Heb. nouns in the plural.42

In short, something unique seems to be happening here.43 The scribe of Ra 1098 undoubtedly wrote σεσι in the margin. Why is the question. That the antigraph originally had ὑποκρίσεσι in the column of Aquila is not necessarily the best answer. Possibly, the antigraph had σεσι in the margin from some prior “corrector,” although in this case we might expect the scribe of Ra 1098 to write γρ(άφεται) as elsewhere – 32(31):7 (αʹ); 35(34):15 (σʹ), 17 (σʹ) – for an unexpected phenomenon that “is written” so in the manuscript before him. However, were the scribe of Ra 1098 registering an emendation for which he, as a copyist, had no textual precedent, and he therefore felt unfree to modify the text as it stood, perhaps this is what a marginal suggestion would look like as opposed to a correction. We adopt this explanation and leave the noun in question in the singular.

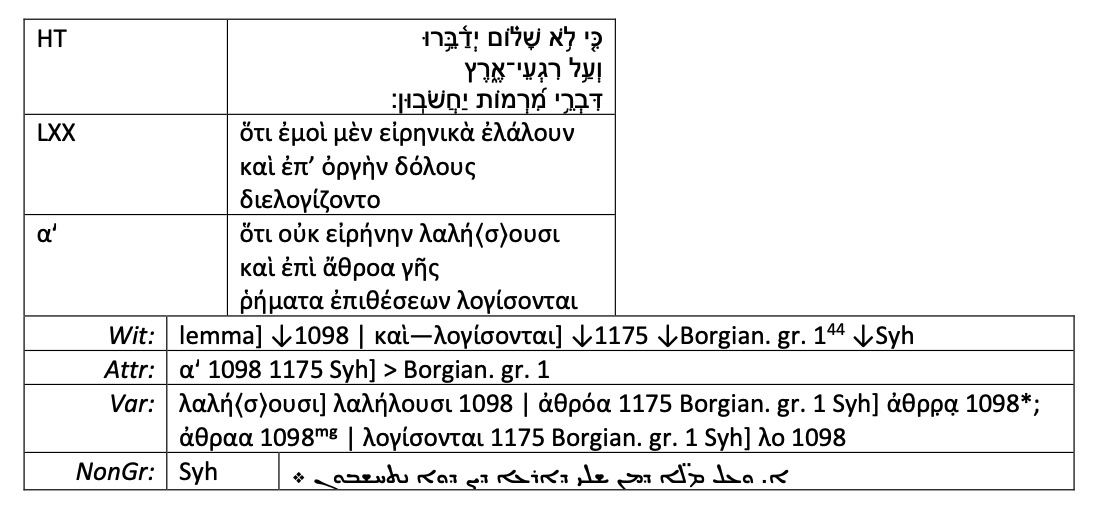

35(34):20 Aq

Mercati transcribes λαλήλουσι as is without writing “sic” in a footnote – his typical procedure when indicating a scribal error. The «Osservazioni» (236–37) discuss λαλήλουσι as if the form under consideration were an unexpected λαλοῦσι. Carrera transcribes λαλήλ̣ουσι and classifies it as a scribal error that apparently combines “the present indicative and the future indicative of ‘λαλέω.’” (287) But the simplest solution is to emend the third lamed to sigma and read it as an error for a future indicative.45

Mercati and Carrera both depict a supralinear alpha above the final letter of ἀθρόα, yet they differ respectively in transcribing the ending as ἀθρό⁎ vs. ἀθρρ̣α̣. While Mercati’s transcription reflects a more expected form, Carrera (287–88) provides a photograph substantiating his choice. Whatever the correct reading of Ra 1098 is, the original reading of Aquila is likely a substantive form of the adjective ἄθροος ‘noiseless’ (the text above represents the corrected accent from ἀθρόα to ἄθροα). The Syh understood it so, unexpectedly taking ἄθροα as modifying ῥήματα while leaving γῆς and ἐπιθέσεων as genitives of a single head phrase; thus, ܡ̈ܠܐ ܕܡܢ ܫܠܝ ܕܐܪܥܐ ܕܨܕܘܐ ‘words (originating) from silence in the land of mockery’ (cf. «Osservazioni», 237–38).

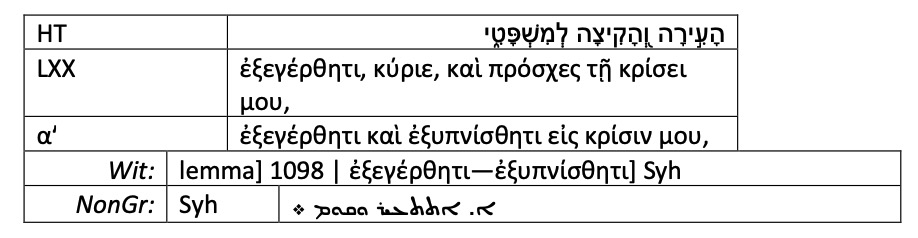

35(34):23a Aq

Mercati transcribes ε̣ἰ̣ς κρ̣ί⁎⁎ and notes that he initially “wrote κρισιν, but it is unclear whether the word ends in σιν or μα.” (57 n.) He attempts to downplay his original transcription by saying the parallel columns influenced him («Osservazioni», 246–47, esp. n. 17). The real reason for his doubt, however, is that Aquila unequivocally translated משׁפט → κρίμα elsewhere, as in 89(88):31, and Mercati does not think it fitting that Aquila would translate a word of such frequency and importance with alternate Grk. terms. Carrera reads ε̣ἰ̣ς κρί̣σιν, without commenting on the variance from Mercati. In this instance, his lack of engagement with translation technique serves us by providing a bias-free transcription. Accordingly, we side with Carrera and Mercati’s initial transcription.

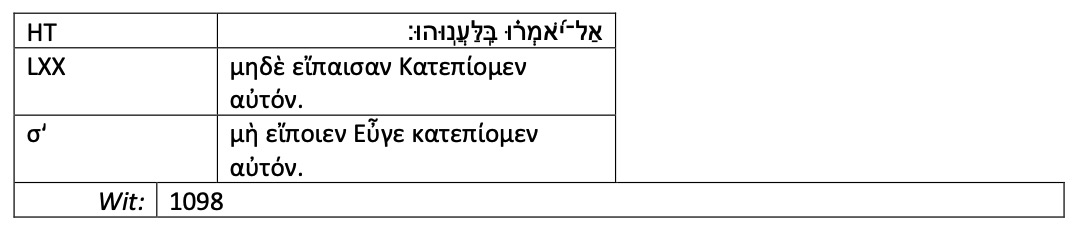

35(34):25b Sym

Busto Saiz omits Εὖγε, following the suggestion of Mercati (59 n.). But the «Osservazioni» (256) can offer no real basis for the decision, besides Εὖγε being a plus – hardly an argument worth buying. We therefore leave the text as it is.

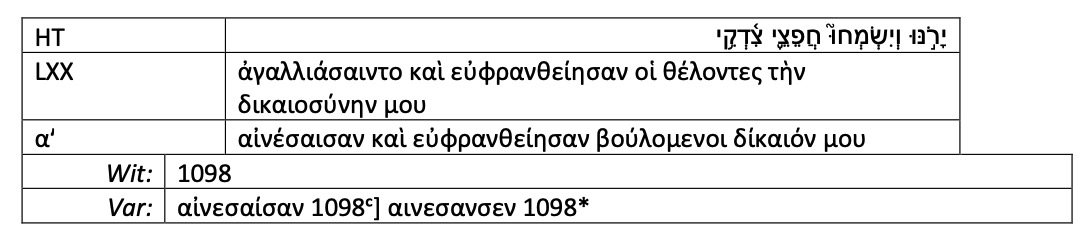

35(34):27a Aq

Mercati gives the (corrected) text as αἰνέσαιεν but elaborates in the «Osservazioni» (261–62) that originally it read αινεσανσαν. In contrast, Carrera gives the corrected reading as αἰνεσαίσαν, the original being αινεσανσεν, and backs up his dissenting assessment with a photograph (292–93).46

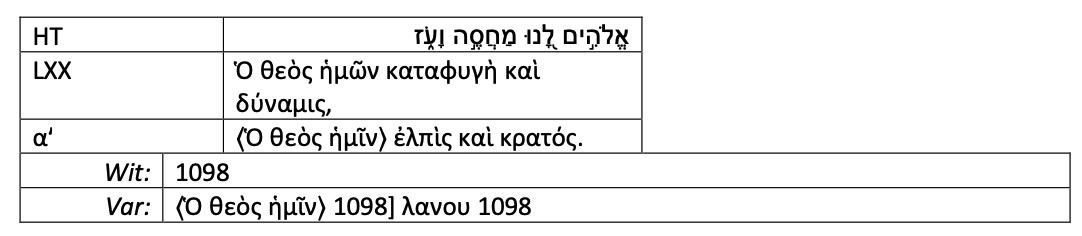

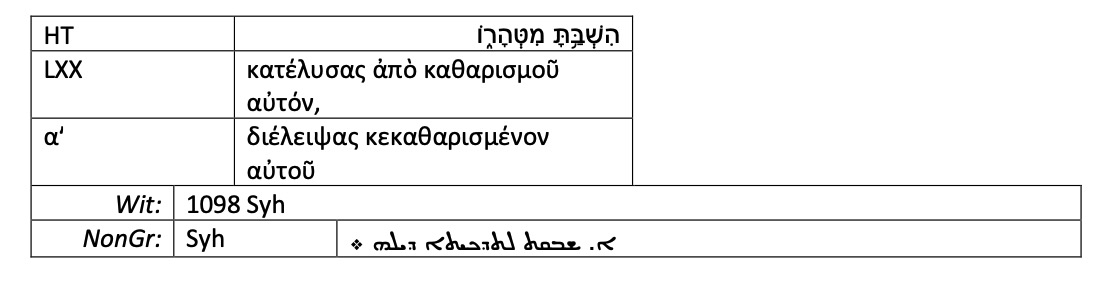

46(45):2a Aq

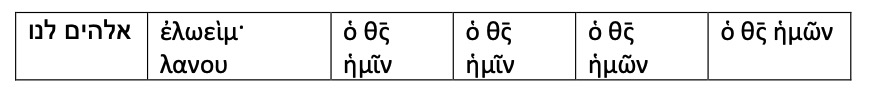

The scribe of Ra 1098 wrote the first line of 46(45):2a as follows:

Table 3: Mercati’s transcription of the first line of Ps 46(45):2a according to Ra 1098

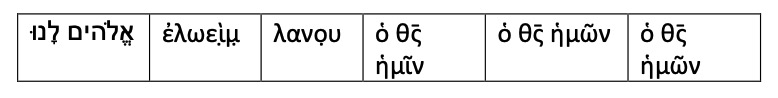

We can only assume accidentally, Carrera without comment transcribes ἡμῶν instead of ἡμῖν for Symmachus. As for the scribe of Ra 1098, he wrote λανου in the second column instead of the first, an unprecedented error in the manuscript (Carrera, 318). The «Osservazioni» (320–21) recommend reconstructing Aquila anarthrously as ⟨θς̄ ἡμῖν⟩.47 However, Aquila did occasionally add the article when not present in אלהים (see 18[17]:29; 46[45]:6bis, 8, 11), so one cannot assume he would not have done so. One can better account for the parablepsis of the scribe if Aquila and Symmachus identically had ὁ θς̄ ἡμῖν. Accordingly, we may reconstruct the first line as follows:

Table 4: A reconstruction of the original first line of the Hexapla of Ps 46(45):2a

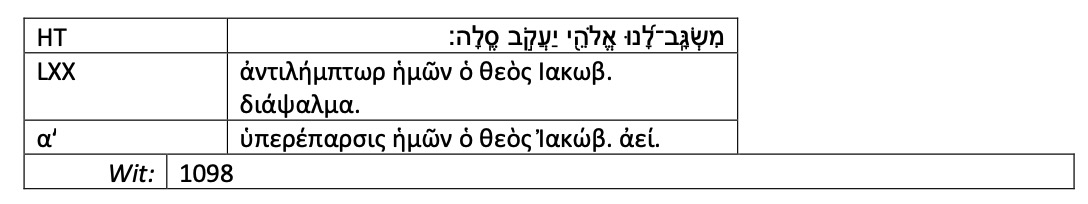

46(45):8b Aq

Mercati transcribes θς̄ Ἰακωβ for Aquila and notes, “The apex clearly seen before θς̄ belongs to Ιακωβ b.” (77 n.; i.e., the preceding column of the Secunda, which reads ἰα̣κὼβ). Carrera, in contrast, transcribes ὁ θς̄ ἰακωβ for Aquila, although he does not explain the change in his commentary. I suspect Mercati tried to justify what he wanted to see: Aquila never adding so much as an article that lacked a correlating morpheme in the Hebrew (cf. 46[45]:2a above).

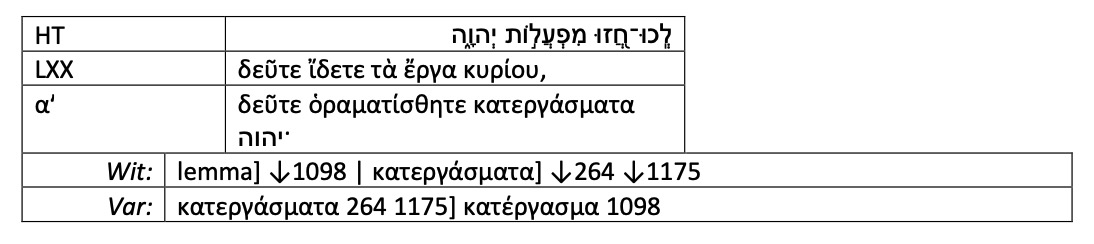

46(45):9a Aq

The original κατεργασματα was likely shortened to κατεργασμα in transmission («Osservazioni», 341),48 although Aquila elsewhere translated a plural Heb. noun in the singular (e.g., 46[45]:5; 49[48]:4). Perhaps we should even explicate it as κατεργάσμα(τα), though Mercati and Carrera identically transcribe Ra 1098 as singular.

46(45):12b Aq

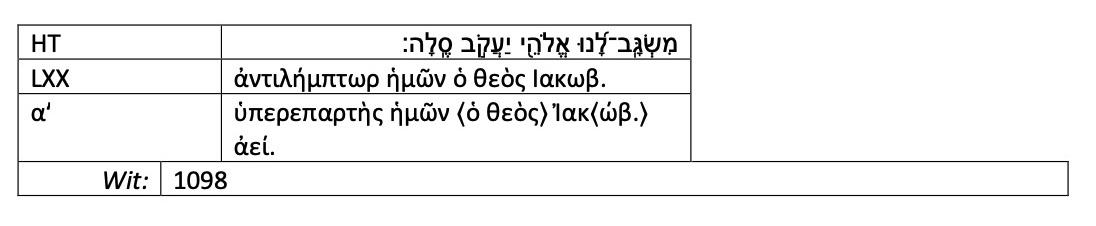

Mercati, whom Carrera follows, supplies the implicit ending of Aquila here as ὑπερεπαρτὴς ἡμ(ῖν), even though Aquila in 46(45):8 explicitly has ὑπερέπαρσ(ις) ἡμῶν. We should allow the repetitive nature of the refrain to guide us in explicating the ending of ἡμ- in v. 12b like the unequivocal genitive of v. 8b. Thus, read ἡμῶν in both cases. And yes, Aquila translated משׂגב differently in both verses!

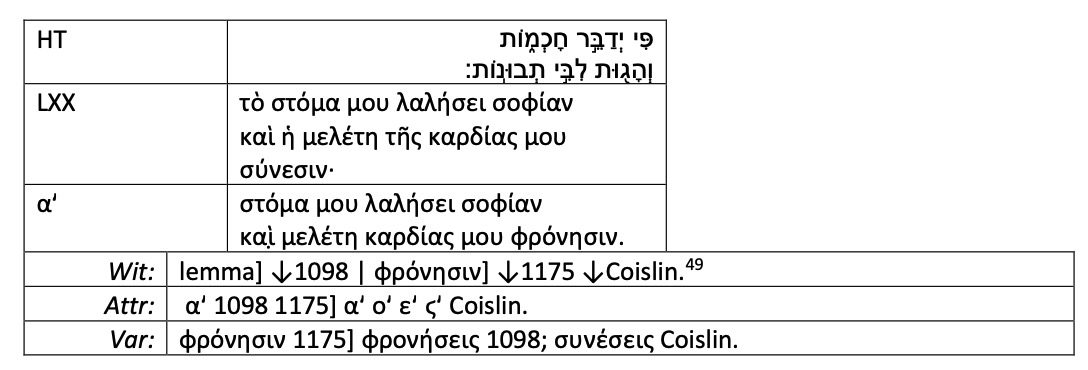

49(48):4b Aq

Rahlfs 1098 plus Coislin. betray influence from the columns of οἱ οʹ and εʹ (= σύνεσεις) by degrees: 1098 only reveals the influence of their plural nominative ending, while Coislin. entirely replaces Aquila with their lemma (cf. «Osservazioni», 379–80). Aquila’s translation presupposes an elliptical construction in the second stichos with יְדַבֵּר → λαλήσει governing both clauses; see similarly 35(34):17; 89(88):26, etc.

49(48):8a Aq

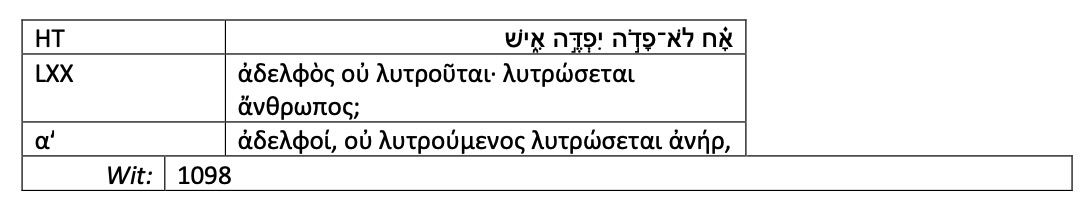

Mercati and Carrera’s transcriptions differ respectively in one letter of one word: ἀδελφος̣ vs. ἀδελφοι̣. The latter comments, “ἀδελφοι—Scribal error. The scribe wrote either ‘ἀδελφοι’ or ‘ἀδελφον.’ Additionally[,] there is no visible accent.” (340–41)50 It would seem Mercati allowed himself to be led by the other columns (all = ἀδελφος) in his transcription. If Aquila indeed translated ἀδελφον, he would be interpreting the preverbal אָ֗ח – note the revia – as a topicalised object, like Barthélemy (288–89) is inclined to interpret the Heb.51 If, however, Aquila translated ἀδελφοί, then he would have modified the number of the noun to match the plural addressees of 49(48):2–3,52 entailing the vocative case, though the plurality of the noun masks it. Repeatedly and unambiguously, Aquila used the vocative for singular addressees elsewhere (30[29]:13bis; 31[30]:6; 35(34):17, etc.). We follow this latter possibility and transcribe ἀδελφοί.

49(48):12a Sym

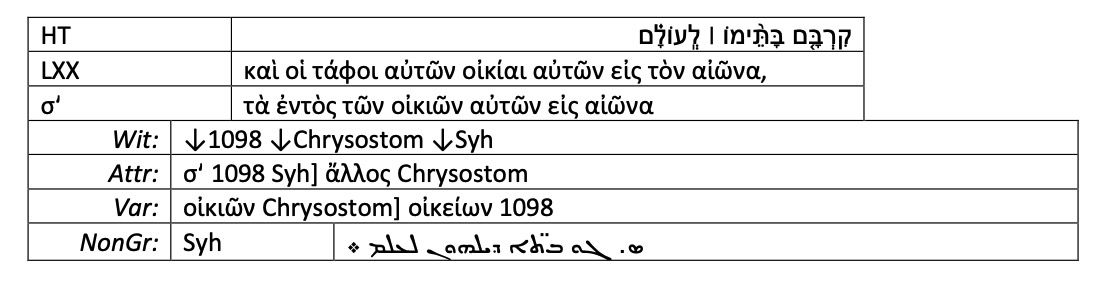

Busto Saiz’ apparatus records “οἰκῶν] οἰκιῶν F,” from whence comes the reading of Chrysostom. It seems Busto Saiz has ignored Mercati’s footnote (89 n.) indicating οἰκείων (= Carrera) as the actual reading. Rahlfs 1098’s οἰκείων reflects a change from Chrysostom’s οἰκιῶν due to iotacism,53 so the two are in fact agreed. Rather than emending οἰκείων (i.e., οἰκία) to the synonymous οἰκῶν (i.e., οἶκος), we would do better to stick with οἰκία.

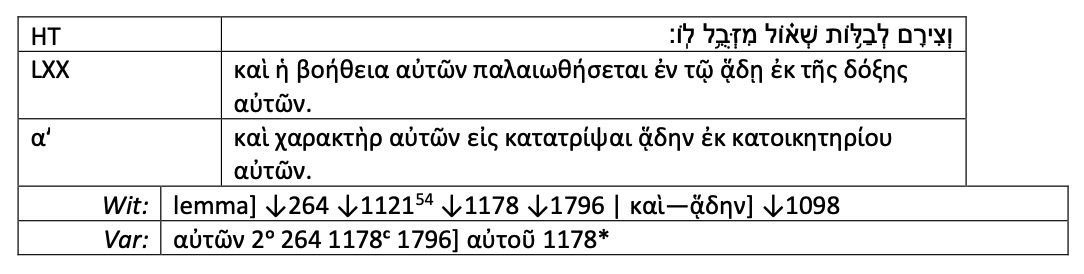

49(48):15c Aq

The «Osservazioni» (406) unnecessarily recommend following the original αὐτοῦ of 1178, which was rightly corrected to the plural (see Barthélemy, 301–03).

49(48):15c Sym

Busto Saiz excludes the full reading of Symmachus from manuscripts beyond Ra 1098 (on which see «Osservazioni», 404–06; Barthélemy, 302), but we incorporate it. One could assume Syh’s ܕܝܠܗܘܢ 2ᵒ entails a variant αὐτῶν, but more likely the Syriac translator harmonised the number to the preceding pronoun.

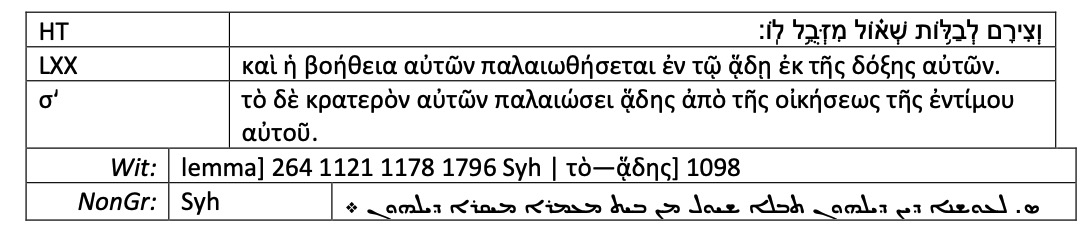

89(88):33a Aq

Carrera transcribes ἀθεσίας and comments (346) that the reading is clear. In contrast, Mercati transcribes ἀθεσίαν̣ and notes (91 n.) that the reading of the nu is uncertain. The «Osservazioni» (411–12) clarify the convoluted attribution of Ra 264 (omitted by Field), which supports the plural reading of Aquila. Hence, Mercati’s expectation of how Aquila would have translated has once again mislead his transcription.

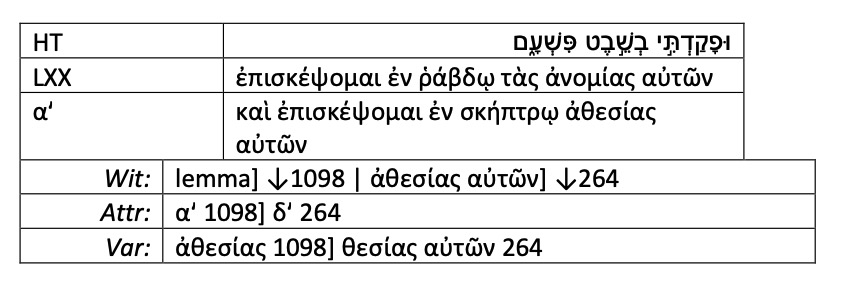

89(88):45a Aq

The text of Aquila simply reads κεκαθαρισμ- without the ending specified. Carrera explicates it as κεκαθαρισμ(όν) and Mercati as κεκαθαρισμόν55 but the latter remarks in a footnote, “Sic. l. κεκαθαρισμ⟨έν⟩ον.” (95 n.) It seems Mercati explicated the ending and forgot he had done so. Regardless, giving the text as κεκαθαρισμός implies an unlikely neologism with the partial reduplication, leaving us with a text that needs “correction” if we follow Mercati.56 We should simply represent Aquila as the perfect passive participle κεκαθαρισμένον.

89(88):46a Aq

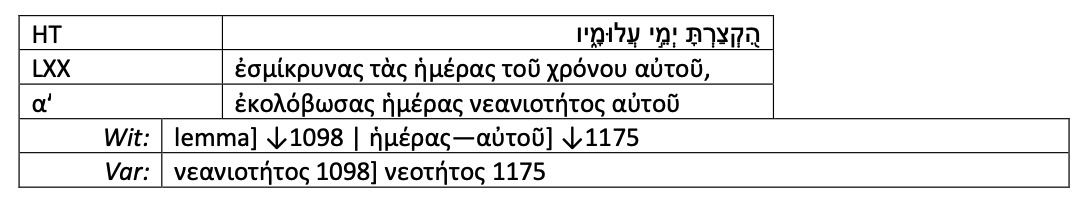

Mercati transcribes Ra 1098 as νεανι̣ο̣τήτ(ων) αὐτ̣οῦ, Carrera differing only in which letters are dubious: νεαν̣ι̣ο̣τήτ(ων) αὐτοῦ. The ending of the lemma in Ra 1175 is also implicit, which the «Osservazioni» (431) plausibly suggest was changed from νεανιοτήτ(ων) to νεοτήτ(ων) due to influence from Symmachus – in Ra 1098, νεό̣τητ̣ο(ς). The question then becomes whether to explicate the lexeme νεανιότης as plural (so Mercati, Carrera, and Field) or singular in both instances.

While the «Osservazioni» (431) correctly observe that Aquila translated עלמות in Pss 9:1 and 46(45):1 with νεανιότης, they fail to acknowledge that in the former instance the Grk. noun is singular but plural only in the latter: עַלְמוּת → νεανιότητος vs. עַֽל־עֲלָמוֹת → ἐπὶ νεανιοτήτων, respectively.57 By comparing Aquila’s translation of the nearly identical Heb. expression in Job 33:25b, יָשׁוּב לִימֵי עֲלוּמָיו → ἐπιστρέψει εἰς ἡμέραν νεανιότητος αὐτοῦ,58 we see a truth evident elsewhere also: Aquila translated plurale tantum nouns as singular or plural contextually. In 89(88):46a, we should explicate Aquila as singular both because of the similarity of the expression in Job 33:25b and because the reading Ra 1175 represents would be easier to explain if the endings of Aquila and Symmachus were both singular.

Conclusion

From the nearly 30 verses presented above, mostly of Aquila but also of Symmachus, several characteristics deserve mention. In many instances (18[17]:34b; 30[29]:6d; 35[34]:16a; 46(45):2a; 49[48]:8a, 15c; 89[88]:33a, 46a), Mercati’s conviction that Aquila should or would have always translated pedantically has hampered his text-critical judgments. The same is true of both Mercati and Busto Saiz in the case of Symmachus for 35(34):25b. On a couple occasions (18[17]:36b, σʹ; 35(34):15, αʹ), the preferable reading reflects a Vorlage different from the Leningrad Codex, which prior editors have been reticent to acknowledge. Finally, Carrera’s recent work repeatedly improves upon Mercati (30[29]:6d; 32[31]:9b–c, 11b; 35[34]:14b, 23a, 27a; 49[48]:8a; 89[88]:33a). The reason I have not emended the text of Ra 2005, preserving portions of Aquila and Symmachus for Ps 22(21):15–18, 20–28, is simple: in the few verses that remain, I would not emend Taylor’s work on Aquila nor Busto Saiz’ on Symmachus.

Whether my efforts constitute a modest contribution toward the ongoing efforts of establishing a critical text of Aquila and Symmachus, I leave to others to decide. At the very least, I have attempted to justify the reasons for my editorial judgments in a way that invites critique. Living in the twilight of the efforts of the Göttinger Septuaginta and Hexapla Project as we do, I hope the present work will anticipate the dawn.

-

My thesis is being conducted under the supervision of Prof. David Shepherd at Trinity College Dublin. The other congeners with whom I am comparing the translation techniques of Aquila and Targum Onqelos are LXX-Numbers, Samaritan Targum MS J (according to Abraham Tal’s sigla), kaige in the βγ section of Reigns, Targum Jonathan, Symmachus, Theodotion, and Old Greek Ecclesiastes. I thank Bryanne Young, my wife, for catching several typos and bringing to my attention an unconscious use of an archaism. My sincerest thanks to Felix Albrecht for welcoming this work as a post on the Göttinger Septuaginta blog and for suggesting numerous improvements. ~ Carpe Deum↩︎

-

A fantastic, accessible, and up-to-date overview of these manuscripts is Felix Albrecht, “The Hexapla of Psalms,” Göttinger Septuaginta, 14 December 2021, https://septuaginta.uni-goettingen.de/blog/the-hexapla-of-psalms/. I remain suspicious of the other contiguous and anonymous translations frequently attributed to Aquila, as per the editions of F. Crawford Burkitt, Fragments of the Books of Kings According to the Translation of Aquila (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1897); Charles Taylor, Hebrew-Greek Cairo Genizah Palimpsests from the Taylor-Schechter Collection, Including a Fragment of the Twenty-Second Psalm According to Origen’s Hexapla (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1900), 55–85; Bernard P. Grenfell and Arthur S. Hunt, The Amherst Papyri: Being an Account of the Greek Papyri in the Collection of Lord Amherst of Hackney. Volume I: Ascension of Isaiah, and Other Theological Fragments with Nine Plates (London: Frowde, 1900), 28–31.↩︎

-

Giovanni Mercati, ed., Psalterii hexapli reliquiae. Pars prima: Codex rescriptus Bybliothecae Ambrosianae O 39 sup., phototypice expressus et transcriptus, Codices ex ecclesiasticis Italiae Bybliothecis delecti phototypice expressi 8 (Vatican Library: Rome, 1958); Taylor, Cairo Genizah Palimpsests.↩︎

-

José Ramón Busto Saiz, La traducción de Símaco en el libro de los Salmos, TECC 22 (Madrid: CSIC, 1978), 389–426.↩︎

-

Frederick Field, Origenis Hexaplorum quae Supersunt: Jobus–Malachias. Auctarium et Indices, vol. 2 (Oxford: Clarendon, 1875); Giovanni Mercati, Psalterii hexapli reliquiae. Pars prima «Osservazioni»: Commento critico al testo dei frammenti esaplari, Codices ex ecclesiasticis Italiae Bybliothecis delecti phototypice expressi 8 (Rome: Vatican Library, 1965).↩︎

-

Roberto Adrian Carrera, “The Mercati Fragments: A New Edition of Rahlfs 1098” (Ph.D. diss., The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, 2022). See further idem, “Codex Ambrosianus O 39 sup. (Ra 1098) and Its Palaeographical Profile,” in Editing the Greek Psalter, ed. Felix Albrecht and Reinhard Gregor Kratz, DSI 18 (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2024), 369–82. Open Access: https://doi.org/10.13109/9783666560941.369. The imaging was carried out by SCHRIFT-BILDER.org.↩︎

-

Carrera, “The Mercati Fragments,” 65–68.↩︎

-

Thus initially, “there are many places where Mercati’s transcription and mine will differ. I have marked most of them in the endnotes with the phrase Contra Mercati”; “The Mercati Fragments,” 66. He later elaborates, “I briefly note any disagreement with Mercati’s edition. In such cases, I have decided to use the phrase Contra Mercati.” Ibid., 182. In actuality, there are repeated instances where Carrera does not comment on his changes respective to Mercati. To illustrate, I cite some instances from Ps 18(17) where Carrera’s text (cited first, followed by :: Mercati’s) differs from Mercati yet he does not acknowledge the differences. We find, e.g., a missing letter with ὑπε̣ραπιστὴς :: ὑπερασπιστής (σʹ v. 31c); a different letter with ἐπιστρέψα :: ἐπιστρέψω (αʹ v. 38b); different accentuation with ἴσχυρὸς :: ἰσχυρός (αʹ v. 31a); or different case with ἀνδρὸ̣ς̣ :: ἄνδρα (σʹ v. 26b). His commentary provides no explanation, which leaves one wondering whether Carrera is creating his own typos or restoring typos found in Ra 1098 that Mercati had corrected.↩︎

-

This is despite the infelicity of Busto Saiz not differentiating between Syriac retroversions and other Greek quotations in his apparatus, all of which he cites indiscriminately as “F[ield].”↩︎

-

See especially John D. Meade, A Critical Edition of the Hexaplaric Fragments of Job 22–42, OHCEEF 1 (Leuven: Peeters, 2020), 18–22.↩︎

-

Alfred Rahlfs, ed., Psalmi cum Odis, SVTG X (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1979).↩︎

-

See Felix Albrecht, “Report on the Göttingen Septuagint,” Text 29.2 (2020): 201–20, https://doi.org/10.1163/2589255X-bja10003.↩︎

-

Field, Origenis Hexaplorum, vol. 2; Taylor, Cairo Genizah Palimpsests; Mercati, Psalterii hexapli reliquiae; Busto Saiz, La traducción de Símaco; Carrera, “The Mercati Fragments.”↩︎

-

Mercati, «Osservazioni».↩︎

-

Dominique Barthélemy, Critique textuelle de l’Ancien Testament, ed. Stephen Desmond Ryan and Adrian Schenker, vol. 4: Psaumes of OBO 50/4 (Fribourg: Academic Press; Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2005). Open Access: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-150304.↩︎

-

Mercati’s edition numbers footnotes by column (“b.” for the Secunda, “c.” for Aquila, “d.” for Symmachus, etc.) and superscript line numbers. For simplicity, I cite these by page number and “n.”↩︎

-

On which see the beta version of the Göttinger Septuaginta’s “Manuscript Catalogue”: https://septuaginta.uni-goettingen.de/catalogue/.↩︎

-

Where Field regularly cites “Montef.,” “Nobil.,” “Vat.,” etc., the «Osservazioni» attempt to specify the sources behind these references.↩︎

-

There are slight orthographical differences between the two repeated lines which deserves attention beyond what we can offer here.↩︎

-

The scribe of Ra 1098 frequently makes a word break when a column ends with οὐκ, ending one line with οὐ- and beginning the next with -κ. In this instance, he ended the line with καὶ οὐ and subconsciously expanded the beginning of the next from κ to καὶ; see Mercati (21 n.).↩︎

-

For the sake of the uninitiated, Mercati (and Carrera) follow Field’s practice of representing abbreviated information in parentheses (). Rahlfs 1098 also uses nomina sacra, but we are here speaking of instances where entire functors – mostly καί – or parts of words – especially case markings – were cut off to save space.↩︎

-

Of the three, Mercati only corrects this instance and notes “Sic bis.” (87 n.)↩︎

-

Mercati (21 n.) plausibly suggests that the other columns agreed with the οἱ οʹ, yet I leave that to others to decide.↩︎

-

Carrera makes both these adjustments without commenting on them.↩︎

-

These additional challenges need not detain us as they extend beyond the scope of our purpose. Rahlfs 1098 correctly represents Aquila.↩︎

-

For a full picture, one must further consult Field’s appendix, “Auctarium ad Origenis Hexapla,” 16. Apart from consulting the «Osservazioni», the Göttinger Septuaginta’s beta “Hexapla Database” (processing date 11 November 2023) helpfully portrays the evidence of Ra 264:

https://septuaginta.uni-goettingen.de/hexapla?ref=Ps.31.9. Retrieved 23 September 2024.↩︎ -

Mercati clarifies in a footnote (43 n.) that though the initial ε is apparent, the next two letters are not, which he believes to have been ις (hence, εἰσεπιστρέψαι).↩︎

-

Meade’s new edition corrects Ra 252’s attribution to περιστρέψεται from Field’s περιστρέφεται; Meade, Hexaplaric Fragments of Job 22–42, 273. Perhaps Field’s eyes misled him due to expecting Aquila to translate the Heb. participle in the present rather than future tense.↩︎

-

Even the «Osservazioni» are disinclined to accept εἰσεπιστρέψαι, which is now a moot point if Carrera’s transcription is correct.↩︎

-

“ThM” = Theodore of Mopsuestia as per Robert Devreesse, Le commentaire de Théodore de Mopsueste sur les Psaumes (I-LXXX), StT 93 (Vatican City: Vatican Library, 1939), 141. Quoted from the «Osservazioni» (175).↩︎

-

Field presents the materials of Ra 264 as if it gave three attributions to Aquila: αʹ αἰνοποιήσατε. αʹ αἰνοποιεῖτε. αʹ αἰνεῖτε; “Auctarium ad Origenis Hexapla,” 16. However, the reading αʹ αἰνεῖτε actually comes from the next verse, 33(32):1 (so «Osservazioni», 174).↩︎

-

Carrera incorrectly locates it in his edition at l. 9 of col. 2 instead of l. 10.↩︎

-

Sic; Carrera’s edition transcribes κατέ̣κ̣υψα while he gives κατέ̣[κ]υψα in his commentary.↩︎

-

The «Osservazioni» do not mention Barhebraeus, although Field does.↩︎

-

Quoted from Brill’s Dead Sea Scrolls Electronic Library: https://brill.com/display/package/dsso?language=en.↩︎

-

This also hints at the fuller reading of Symmachus, as per Busto Saiz’ critical text, entailing a Vorlage identical to the Tiberian Μasoretic text: σκάζοντος δέ μου ηὐφραίνοντο καὶ ἠθροίζοντο, συγήγοντο κατ’ ἐμοῦ πλῆκται, καὶ οὐκ ᾔδειν, ἀπορρήσαντες οὐκ ἠρέμουν.↩︎

-

For εʹ, ἐσιώτησαν sic; read ἐσιώπησαν.↩︎

-

For ϛʹ, κατ ́ έμοῦ and κατε̣νύγησ(σαν) sic; read κατ’ ἐμοῦ and κατε̣νύγησ(σαν). For οἱ οʹ, μάστηγες sic; read μάστιγες.↩︎

-

Kennicott MS 147 also repeats נכים ולא, hinting at carelessness in other respects.↩︎

-

One can confirm this easily by searching “scribal correction” in Carrera and browsing the results.↩︎

-

Carrera comments, “This is the first instance of that [sublinear] placement. Usually, the corrected reading is placed on the right side of the column.” (318) The “usual” placement “on the right side of the column” is not born out by the evidence he presents elsewhere, and one wonders whether he has the marginal readings of θʹ and ϛʹ in mind. The only other instance he presents of a correction beside the line comes from Ps 49(48):4 in the column of οἱ οʹ with σύνεσεις in the text and σύνεσιν in the margin (p. 339). Why this should not be taken as a reading of θʹ is unclear to me.↩︎

-

The evidence that Aquila elsewhere changes the number of nouns – see 46(45):9a below – cuts both ways: it could be taken as proof that he otherwise does alter grammatical number, yet it could also be taken as proof that the scribe elsewhere does not “correct” Aquila to match the grammatical number of the Hebrew. We acknowledge the conundrum and move along.↩︎

-

Unfortunately, Carrera does not comment on this marginalia since he represents it identically to Mercati.↩︎

-

The reading of “Borgian. gr. 1” (Nᵒ diktyon: 65154) comes from the «Osservazioni» (236).↩︎

-

Without having access to the photographs, I cannot help but wonder whether the text simply reads the sigma, but visual factors have impaired our ability to see this clearly.↩︎

-

As he notes, the acute accent in the manuscript is incorrectly placed. I have corrected the text as I represent it above.↩︎

-

The «Osservazioni» (321; see similarly Field) also suggest emending εὑρέθης̣ to εὑρέθη, but I would sooner suspect that Aquila’s Vorlage read נִמְצָאתָּ or נִמְצָתָּ.↩︎

-

The «Osservazioni» (341; cf. xvi, xix) also attest to “ps. Eracleota” (i.e., “pseudo-Heraclea,” the erstwhile “Theodorus of Heraclea”) identically confirming the readings of Ra 264 1175 – in this case coming from Corderio’s edition of Barber. gr. 525 («Osservazioni», 341 n. 53), which = Nᵒ diktyon: 65068. In the interests of simplicity, I have not included it.↩︎

-

The «Osservazioni» (379) specify beyond Field and Montfaucon that the relevant catena manuscript of “Coislin.” is potentially Ra 187 or 190.↩︎

-

His text has the “doubting dot” but the lemma in the commentary does not, as presented above.↩︎

-

For characteristics of topicalisation and left dislocation in Biblical Hebrew, see Cynthia L. Miller-Naudé and Jacobus A. Naudé, “Differentiating Left Dislocation Constructions in Biblical Hebrew,” in New Perspectives in Biblical and Rabbinic Hebrew, ed. Aaron D. Hornkohl and Geoffrey Khan, CSLS 7 (Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 2021), 619–24. Open Access: https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0250.20.↩︎

-

On the possibility of a common noun being an anarthrous vocative, see Cynthia L. Miller-Naudé, “Definiteness and the Vocative in Biblical Hebrew,” JNSL 36.1 (2010): 43–64; idem, “Vocative Syntax in Biblical Hebrew Prose and Poetry: A Preliminary Analysis,” JSS 55.2 (2010): 347–64, https://doi.org/10.1093/jss/fgq002.↩︎

-

On which see John William Wevers, “A Note on Scribal Error,” Canadian Journal of Linguistics 17.2–3 (1972): 189, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008413100007131.↩︎

-

The reading of Ra 1121 comes not from the «Osservazioni» (404–06) but Barthélemy (302).↩︎

-

The acute accent as both Mercati and Carrera give it is indeed acute.↩︎

-

Barthélemy (628–30) represents Aquila as does Mercati, uncharacteristically refraining from showing whether Aquila supports the Tiberian Masoretic text or not. He merely indicates the text of Aquila is corrupt. Reider-Turner, in contrast, does not give an entry for κεκαθαρισμός but instead gives καθαρισμός as Aquila’s translation of “נָקָה inf. Ps. lxxxviii (lxxxix) 44 [sic; read 45],” following Field’s retroversion of the Syh; Joseph Reider and Nigel Turner, An Index to Aquila: Greek-Hebrew; Hebrew-Greek; Latin-Hebrew with the Syriac and Armenian Evidence, VTSup 12 (Leiden: Brill, 1966), 121; cf. 133.↩︎

-

In both instances, the Secunda is αλμωθ («Osservazioni», 431), showing that Aquila was not alone in vocalising Ps 9:1 differently.↩︎

-

See Meade, Hexaplaric Fragments of Job 22–42, 199. I have expressed my doubts to Dr. Meade of his assessment that νεανιότητος is rightly attributed to Theodotion. Rather, I believe that the variant νεότητος (= all besides 788ʹ 3005) represents Theodotion, which was Theodotion’s translation in Job 20:11a. Aquila and Theodotion are in all other respects equal in Job 33:25b. Reider would then still be correct in stipulating that no translator besides Aquila used νεανιότης; Joseph Reider, Prolegomena to a Greek-Hebrew & Hebrew-Greek Index to Aquila (Philadelphia: Oxford University Press, 1916), 124; cf. 115. Cf. also José Ramón Busto Saiz, “El léxico peculiar del traductor Aquila,” Emerita 48.1 (1980): 36–37, https://doi.org/110.3989/emerita.1980.v48.i1.837.↩︎

by Jonathan Groß and Peter Schreiner, January 20, 2026

by Bonifatia Gesche, December 23, 2025

by Matteo Domenico Varca, November 30, 2025

by Anna Kharanauli, October 31, 2025

by Jonathan Groß, September 26, 2025

by Felix Albrecht, August 31, 2025

by Vadim Wittkowsky, July 31, 2025